- Home

- Jack London

The Turtles of Tasman Page 5

The Turtles of Tasman Read online

Page 5

*********

He was very much disturbed to-day. He could not write, for I had made the servant carry the pen out of the room in his pocket But neither could I write.

*********

The servant never sees him. This is strange. Have I developed a keener sight for the unseen? Or rather does it not prove the phantom to be what it is-a product of my own morbid consciousness?

*********

He has stolen my pen again. Hallucinations cannot steal pens. This is unanswerable. And yet I cannot keep the pen always out of the room. I want to write myself.

*********

I have had three different servants since my trouble came upon me, and not one has seen him. Is the verdict of their senses right? And is that of mine wrong? Nevertheless, the ink goes too rapidly. I fill my pen more often than is necessary. And furthermore, only to-day I found my pen out of order. I did not break it.

*********

I have spoken to him many times, but he never answers. I sat and watched him all morning. Frequently he looked at me, and it was patent that he knew me.

*********

By striking the side of my head violently with the heel of my hand, I can shake the vision of him out of my eyes. Then I can get into the chair; but I have learned that I must move very quickly in order to accomplish this. Often he fools me and is back again before I can sit down.

*********

It is getting unbearable. He is a jack-in-the-box the way he pops into the chair. He does not assume form slowly. He pops. That is the only way to describe it. I cannot stand looking at him much more. That way lies madness, for it compels me almost to believe in the reality of what I know is not. Besides, hallucinations do not pop.

*********

Thank God he only manifests himself in the chair. As long as I occupy the chair I am quit of him.

*********

My device for dislodging him from the chair by striking my head, is failing. I have to hit much more violently, and I do not succeed perhaps more than once in a dozen trials. My head is quite sore where I have so repeatedly struck it. I must use the other hand.

*********

My brother was right. There is an unseen world. Do I not see it? Am I not cursed with the seeing of it all the time? Call it a thought, an idea, anything you will, still it is there. It is unescapable. Thoughts are entities. We create with every act of thinking. I have created this phantom that sits in my chair and uses my ink. Because I have created him is no reason that he is any the less real. He is an idea; he is an entity: ergo, ideas are entities, and an entity is a reality.

*********

Query: If a man, with the whole historical process behind him, can create an entity, a real thing, then is not the hypothesis of a Creator made substantial? If the stuff of life can create, then it is fair to assume that there can be a He who created the stuff of life. It is merely a difference of degree. I have not yet made a mountain nor a solar system, but I have made a something that sits in my chair. This being so, may I not some day be able to make a mountain or a solar system?

*********

All his days, down to to-day, man has lived in a maze. He has never seen the light. I am convinced that I am beginning to see the light-not as my brother saw it, by stumbling upon it accidentally, but deliberately and rationally. My brother is dead. He has ceased. There is no doubt about it, for I have made another journey down into the cellar to see. The ground was untouched. I broke it myself to make sure, and I saw what made me sure. My brother has ceased, yet have I recreated him. This is not my old brother, yet it is something as nearly resembling him as I could fashion it. I am unlike other men. I am a god. I have created.

*********

Whenever I leave the room to go to bed, I look back, and there is my brother sitting in the chair. And then I cannot sleep because of thinking of him sitting through all the long night-hours. And in the morning, when I open the study door, there he is, and I know he has sat there the night long.

*********

I am becoming desperate from lack of sleep. I wish I could confide in a physician.

*********

Blessed sleep! I have won to it at last. Let me tell you. Last night I was so worn that I found myself dozing in my chair. I rang for the servant and ordered him to bring blankets. I slept. All night was he banished from my thoughts as he was banished from my chair. I shall remain in it all day. It is a wonderful relief.

*********

It is uncomfortable to sleep in a chair. But it is more uncomfortable to lie in bed, hour after hour, and not sleep, and to know that he is sitting there in the cold darkness.

*********

It is no use. I shall never be able to sleep in a bed again. I have tried it now, numerous times, and every such night is a horror. If I could but only persuade him to go to bed! But no. He sits there, and sits there-I know he does-while I stare and stare up into the blackness and think and think, continually think, of him sitting there. I wish I had never heard of the eternity of forms.

*********

The servants think I am crazy. That is but to be expected, and it is why I have never called in a physician.

*********

I am resolved. Henceforth this hallucination ceases. From now on I shall remain in the chair. I shall never leave it. I shall remain in it night and day and always.

*********

I have succeeded. For two weeks I have not seen him. Nor shall I ever see him again. I have at last attained the equanimity of mind necessary for philosophic thought. I wrote a complete chapter to-day.

*********

It is very wearisome, sitting in a chair. The weeks pass, the months come and go, the seasons change, the servants replace each other, while I remain. I only remain. It is a strange life I lead, but at least I am at peace.

*********

He comes no more. There is no eternity of forms. I have proved it. For nearly two years now, I have remained in this chair, and I have not seen him once. True, I was severely tried for a time. But it is clear that what I thought I saw was merely hallucination. He never was. Yet I do not leave the chair. I am afraid to leave the chair.

TOLD IN THE DROOLING WARD

Me? I'm not a drooler. I'm the assistant, I don't know what Miss Jones or Miss Kelsey could do without me. There are fifty-five low-grade droolers in this ward, and how could they ever all be fed if I wasn't around? I like to feed droolers. They don't make trouble. They can't. Something's wrong with most of their legs and arms, and they can't talk. They're very low-grade. I can walk, and talk, and do things. You must be careful with the droolers and not feed them too fast. Then they choke. Miss Jones says I'm an expert. When a new nurse comes I show her how to do it. It's funny watching a new nurse try to feed them. She goes at it so slow and careful that supper time would be around before she finished shoving down their breakfast. Then I show her, because I'm an expert. Dr. Dalrymple says I am, and he ought to know. A drooler can eat twice as fast if you know how to make him.

My name's Tom. I'm twenty-eight years old. Everybody knows me in the institution. This is an institution, you know. It belongs to the State of California and is run by politics. I know. I've been here a long time. Everybody trusts me. I run errands all over the place, when I'm not busy with the droolers. I like droolers. It makes me think how lucky I am that I ain't a drooler.

I like it here in the Home. I don't like the outside. I know. I've been around a bit, and run away, and adopted. Me for the Home, and for the drooling ward best of all. I don't look like a drooler, do I? You can tell the difference soon as you look at me. I'm an assistant, expert assistant. That's going some for a feeb. Feeb? Oh, that's feeble-minded. I thought you knew. We're all feebs in here.

But I'm a high-grade feeb. Dr. Dalrymple says I'm too smart to be in the Home, but I never let on. It's a pretty good place. And I don't throw fits like lots of the feebs. You see that house up there through the trees. The high-grade epilecs all live in it by themselves. They're

stuck up because they ain't just ordinary feebs. They call it the club house, and they say they're just as good as anybody outside, only they're sick. I don't like them much. They laugh at me, when they ain't busy throwing fits. But I don't care. I never have to be scared about falling down and busting my head. Sometimes they run around in circles trying to find a place to sit down quick, only they don't. Low-grade epilecs are disgusting, and high-grade epilecs put on airs. I'm glad I ain't an epilec. There ain't anything to them. They just talk big, that's all.

Miss Kelsey says I talk too much. But I talk sense, and that's more than the other feebs do. Dr. Dalrymple says I have the gift of language. I know it. You ought to hear me talk when I'm by myself, or when I've got a drooler to listen. Sometimes I think I'd like to be a politician, only it's too much trouble. They're all great talkers; that's how they hold their jobs.

Nobody's crazy in this institution. They're just feeble in their minds. Let me tell you something funny. There's about a dozen high-grade girls that set the tables in the big dining room. Sometimes when they're done ahead of time, they all sit down in chairs in a circle and talk. I sneak up to the door and listen, and I nearly die to keep from laughing. Do you want to know what they talk? It's like this. They don't say a word for a long time. And then one says, "Thank God I'm not feeble-minded." And all the rest nod their heads and look pleased. And then nobody says anything for a time. After which the next girl in the circle says, "Thank God I'm not feeble-minded," and they nod their heads all over again. And it goes on around the circle, and they never say anything else. Now they're real feebs, ain't they? I leave it to you. I'm not that kind of a feeb, thank God.

Sometimes I don't think I'm a feeb at all. I play in the band and read music. We're all supposed to be feebs in the band except the leader. He's crazy. We know it, but we never talk about it except amongst ourselves. His job is politics, too, and we don't want him to lose it. I play the drum. They can't get along without me in this institution. I was sick once, so I know. It's a wonder the drooling ward didn't break down while I was in hospital.

I could get out of here if I wanted to. I'm not so feeble as some might think. But I don't let on. I have too good a time. Besides, everything would run down if I went away. I'm afraid some time they'll find out I'm not a feeb and send me out into the world to earn my own living. I know the world, and I don't like it. The Home is fine enough for me.

You see how I grin sometimes. I can't help that. But I can put it on a lot. I'm not bad, though. I look at myself in the glass. My mouth is funny, I know that, and it lops down, and my teeth are bad. You can tell a feeb anywhere by looking at his mouth and teeth. But that doesn't prove I'm a feeb. It's just because I'm lucky that I look like one.

I know a lot. If I told you all I know, you'd be surprised. But when I don't want to know, or when they want me to do something I don't want to do, I just let my mouth lop down and laugh and make foolish noises. I watch the foolish noises made by the low-grades, and I can fool anybody. And I know a lot of foolish noises. Miss Kelsey called me a fool the other day. She was very angry, and that was where I fooled her.

Miss Kelsey asked me once why I don't write a book about feebs. I was telling her what was the matter with little Albert. He's a drooler, you know, and I can always tell the way he twists his left eye what's the matter with him. So I was explaining it to Miss Kelsey, and, because she didn't know, it made her mad. But some day, mebbe, I'll write that book. Only it's so much trouble. Besides, I'd sooner talk.

Do you know what a micro is? It's the kind with the little heads no bigger than your fist. They're usually droolers, and they live a long time. The hydros don't drool. They have the big heads, and they're smarter. But they never grow up. They always die. I never look at one without thinking he's going to die. Sometimes, when I'm feeling lazy, or the nurse is mad at me, I wish I was a drooler with nothing to do and somebody to feed me. But I guess I'd sooner talk and be what I am.

Only yesterday Doctor Dalrymple said to me, "Tom," he said, "I just don't know what I'd do without you." And he ought to know, seeing as he's had the bossing of a thousand feebs for going on two years. Dr. Whatcomb was before him. They get appointed, you know. It's politics. I've seen a whole lot of doctors here in my time. I was here before any of them. I've been in this institution twenty-five years. No, I've got no complaints. The institution couldn't be run better.

It's a snap to be a high-grade feeb. Just look at Doctor Dalrymple. He has troubles. He holds his job by politics. You bet we high-graders talk politics. We know all about it, and it's bad. An institution like this oughtn't to be run on politics. Look at Doctor Dalrymple. He's been here two years and learned a lot. Then politics will come along and throw him out and send a new doctor who don't know anything about feebs.

I've been acquainted with just thousands of nurses in my time. Some of them are nice. But they come and go. Most of the women get married. Sometimes I think I'd like to get married. I spoke to Dr. Whatcomb about it once, but he told me he was very sorry, because feebs ain't allowed to get married. I've been in love. She was a nurse. I won't tell you her name. She had blue eyes, and yellow hair, and a kind voice, and she liked me. She told me so. And she always told me to be a good boy. And I was, too, until afterward, and then I ran away. You see, she went off and got married, and she didn't tell me about it.

I guess being married ain't what it's cracked up to be. Dr. Anglin and his wife used to fight. I've seen them. And once I heard her call him a feeb. Now nobody has a right to call anybody a feeb that ain't. Dr. Anglin got awful mad when she called him that. But he didn't last long. Politics drove him out, and Doctor Mandeville came. He didn't have a wife. I heard him talking one time with the engineer. The engineer and his wife fought like cats and dogs, and that day Doctor Mandeville told him he was damn glad he wasn't tied to no petticoats. A petticoat is a skirt. I knew what he meant, if I was a feeb. But I never let on. You hear lots when you don't let on.

I've seen a lot in my time. Once I was adopted, and went away on the railroad over forty miles to live with a man named Peter Bopp and his wife. They had a ranch. Doctor Anglin said I was strong and bright, and I said I was, too. That was because I wanted to be adopted. And Peter Bopp said he'd give me a good home, and the lawyers fixed up the papers.

But I soon made up my mind that a ranch was no place for me. Mrs. Bopp was scared to death of me and wouldn't let me sleep in the house. They fixed up the woodshed and made me sleep there. I had to get up at four o'clock and feed the horses, and milk cows, and carry the milk to the neighbours. They called it chores, but it kept me going all day. I chopped wood, and cleaned chicken houses, and weeded vegetables, and did most everything on the place. I never had any fun. I hadn't no time.

Let me tell you one thing. I'd sooner feed mush and milk to feebs than milk cows with the frost on the ground. Mrs. Bopp was scared to let me play with her children. And I was scared, too. They used to make faces at me when nobody was looking, and call me "Looney." Everybody called me Looney Tom. And the other boys in the neighbourhood threw rocks at me. You never see anything like that in the Home here. The feebs are better behaved.

Mrs. Bopp used to pinch me and pull my hair when she thought I was too slow, and I only made foolish noises and went slower. She said I'd be the death of her some day. I left the boards off the old well in the pasture, and the pretty new calf fell in and got drowned. Then Peter Bopp said he was going to give me a licking. He did, too. He took a strap halter and went at me. It was awful. I'd never had a licking in my life. They don't do such things in the Home, which is why I say the Home is the place for me.

I know the law, and I knew he had no right to lick me with a strap halter. That was being cruel, and the guardianship papers said he mustn't be cruel. I didn't say anything. I just waited, which shows you what kind of a feeb I am. I waited a long time, and got slower, and made more foolish noises; but he wouldn't, send me back to the Home, which was what I wanted. But one day, it was the first of the mont

h, Mrs. Brown gave me three dollars, which was for her milk bill with Peter Bopp. That was in the morning. When I brought the milk in the evening I was to bring back the receipt. But I didn't. I just walked down to the station, bought a ticket like any one, and rode on the train back to the Home. That's the kind of a feeb I am.

Doctor Anglin was gone then, and Doctor Mandeville had his place. I walked right into his office. He didn't know me. "Hello," he said, "this ain't visiting day." "I ain't a visitor," I said. "I'm Tom. I belong here." Then he whistled and showed he was surprised. I told him all about it, and showed him the marks of the strap halter, and he got madder and madder all the time and said he'd attend to Mr. Peter Bopp's case.

The Son of the Wolf

The Son of the Wolf The Iron Heel

The Iron Heel Before Adam

Before Adam Smoke Bellew

Smoke Bellew The Call of the Wild

The Call of the Wild The Valley of the Moon Jack London

The Valley of the Moon Jack London Burning Daylight

Burning Daylight The Sea Wolf

The Sea Wolf White Fang

White Fang A Daughter of the Snows

A Daughter of the Snows The Night-Born

The Night-Born A Son Of The Sun

A Son Of The Sun Dutch Courage and Other Stories

Dutch Courage and Other Stories The People of the Abyss

The People of the Abyss Michael, Brother of Jerry

Michael, Brother of Jerry Love of Life, and Other Stories

Love of Life, and Other Stories Lost Face

Lost Face The Road

The Road Love of Life

Love of Life The Turtles of Tasman

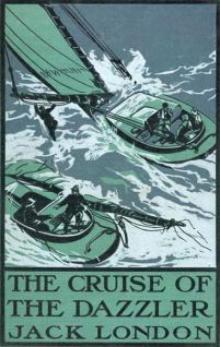

The Turtles of Tasman The Cruise of The Dazzler

The Cruise of The Dazzler The Heathen

The Heathen The Scab

The Scab The Faith of Men

The Faith of Men Adventure

Adventure The Assassination Bureau, Ltd.

The Assassination Bureau, Ltd. The Call of the Wild, White Fang, and Other Stories

The Call of the Wild, White Fang, and Other Stories The Call of the Wild and Selected Stories

The Call of the Wild and Selected Stories Jerry of the Islands

Jerry of the Islands Hearts of Three

Hearts of Three The House of Pride

The House of Pride Moon-Face and Other Stories

Moon-Face and Other Stories Children of the Frost

Children of the Frost South Sea Tales

South Sea Tales The Strength of the Strong

The Strength of the Strong The Jacket (The Star-Rover)

The Jacket (The Star-Rover) The Little Lady of the Big House

The Little Lady of the Big House John Barleycorn

John Barleycorn ADaugter of Snows

ADaugter of Snows The Mutiny of the Elsinore

The Mutiny of the Elsinore Northland Stories

Northland Stories Tales of the Fish Patrol

Tales of the Fish Patrol Call of the Wild and White Fang (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Call of the Wild and White Fang (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Valley of the Moon

The Valley of the Moon The Cruise of the Snark

The Cruise of the Snark The Game

The Game An Autobiography of Jack London

An Autobiography of Jack London