- Home

- Jack London

Call of the Wild and White Fang (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Call of the Wild and White Fang (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Read online

Table of Contents

From the Pages of The Call of the Wild

From the Pages of White Fang

Title Page

Copyright Page

Jack London

The World of Jack London, The Call of the Wild, and White Fang

Introduction

The Call of the Wild

I - Into the Primitive

II - The Law of Club and Fang

III - The Dominant Primordial Beast

IV - Who Has Won to Mastership

V - The Toil of Trace and Trail

VI - For the Love of a Man

VII - The Sounding of the Call

White Fang

Part One - THE WILD

I - The Trail of the Meat

II - The She-Wolf

III - The Hunger Cry

Part Two - BORN OF THE WILD

I - The Battle of the Fangs

II - The Lair

III - The Gray Cub

IV - The Wall of the World

V - The Law of Meat

Part Three - THE GODS OF THE WILD

I - The Makers of Fire

II - The Bondage

III - The Outcast

IV - The Trail of the Gods

V - The Covenant

VI - The Famine

Part Four - THE SUPERIOR GODS

I - The Enemy of His Kind

II - The Mad God

III - The Reign of Hate

IV - The Clinging Death

V - The Indomitable

VI - The Love-Master

Part Five - THE TAME

I - The Long Trail

II - The Southland

III - The God’s Domain

IV - The Call of Kind

V - The Sleeping Wolf

Endnotes

Inspired by The Call of the Wild and White Fang

Comments & Questions

For Further Reading

From the Pages of

The Call of the Wild

He had learned to trust in men he knew, and to give them credit for a wisdom that outreached his own. But when the ends of the rope were placed in the stranger’s hands, he growled menacingly. (page 7)

He saw, once for all, that he stood no chance against a man with a club. He had learned the lesson, and in all his after life he never forgot it. That club was a revelation. It was his introduction to the reign of primitive law, and he met the introduction half-way. (page 12)

There is an ecstasy that marks the summit of life, and beyond which life cannot rise. And such is the paradox of living, this ecstasy comes when one is most alive, and it comes as a complete forgetfulness that one is alive. (page 32)

They were not half living, or quarter living. They were simply so many bags of bones in which sparks of life fluttered faintly. When a halt was made, they dropped down in the traces like dead dogs, and the spark dimmed and paled and seemed to go out. (page 53)

Deep in the forest a call was sounding, and as often as he heard this call, mysteriously thrilling and luring, he felt compelled to turn his back upon the fire and the beaten earth around it, and to plunge into the forest, and on and on, he knew not where or why; nor did he wonder where or why, the call sounding imperiously, deep in the forest. (page 60)

From the Pages of

White Fang

Daylight came at nine o‘clock. At midday the sky to the south warmed to rose-color, and marked where the bulge of the earth intervened between the meridian sun and the northern world. But the rose-color swiftly faded. The gray light of day that remained lasted until three o’clock, when it, too, faded, and the pall of the Arctic night descended upon the lone and silent land. (page 98)

Fear!—that legacy of the Wild which no animal may escape nor exchange for pottage. (page 140)

He had no conscious knowledge of death, but like every animal of the Wild, he possessed the instinct of death. To him it stood as the greatest of hurts. It was the very essence of the unknown; it was the sum of the terrors of the unknown, the one culminating and unthinkable catastrophe that could happen to him, about which he knew nothing and about which he feared everything. (page 146)

He did not like the hands of the man-animals. He was suspicious of them. It was true that they sometimes gave meat, but more often they gave hurt. (page 188)

The clay of White Fang had been molded until he became what he was, morose and lonely, unloving and ferocious, the enemy of all his kind. (page 211)

In a lofty way he received the attentions of the multitudes of strange gods. With condescension he accepted their condescension. (page 273)

The Call of the Wild was first published in 1903. White Fang was first published in 1906.

Introduction, Notes, and For Further Reading

Copyright © 2003 by Tina Gianquitto.

Note on Jack London, The World of Jack London, The Call of the Wild, and White Fang, Inspired by The Call of the Wild and White Fang, and Comments & Questions Copyright @ 2003 by Barnes & Noble, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior written permission of the publisher.

Barnes & Noble Classics and the Barnes & Noble Classics colophon are trademarks of Barnes & Noble, Inc.

The Call of the Wild and White Fang

ISBN 1-59308-200-2

eISBN : 978-1-411-43188-1

LC Control Number 2004100744

Produced and published in conjunction with: Fine Creative Media, Inc. 322 Eighth Avenue New York, NY 10001

Michael J. Fine, President & Publisher

Printed in the United States of America 1 3 5 7 9 10 8642

QM

FIRST PRINTING

Jack London

John Griffith London was born out of wedlock on January 12,1876, in San Francisco. His mother, Flora Wellman Chaney, a spiritualist and music teacher, married John London later that year. John continually moved the family around California looking for work on farms and ranches, and young Jack was self-sufficient by the time he was fourteen. After working as a newspaper delivery boy, cannery worker, and seaman aboard a sealing vessel, in 1894 he joined Coxey’s Army, a group of jobless men, on a march to Washington, D.C., to protest economic conditions. London abandoned the group along the way and eventually served prison time in northern New York for vagrancy. In prison he reflected on his position at the base of the social pyramid as exploited worker and developed his own branch of Socialism, influenced by the writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Nietzsche. He joined the Socialist Labor Party and, espousing the idea that education is the route out of exploitation, enrolled at the University of California at Berkeley. He dropped out after just one semester but continued to educate himself by reading the fiction of such writers as Robert Louis Stevenson, Rudyard Kipling, and Joseph Conrad and the philosophical and political works of Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung, Adam Smith, Immanuel Kant, and Herbert Spencer.

It is telling that when London joined the Klondike Gold Rush in 1897, he packed a copy of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species and John Milton’s Paradise Lost alongside such essentials as bacon and flour. London returned no richer than he was when he left and decided to devote himself to writing. Though London later claimed, “I did not know a soul who had ever published anything... I had no one to give me tips,” in fact he counted among his good friends the poet George Sterling, the writer and journalist Ambrose Bierce, and the editors of the San Francisco Call and the Oakland Times.

He began writing newspaper articles on the Russo-Japanese war and the Mexican Revolution, as well as short stories, and within two decades he had published forty-seven books. By 1913 London was the highest-paid writer in the world, and The Call of the Wild and White Fang were enduringly popular with critics and the public. Both stories draw heavily from London’s Yukon experience and exhibit the influence of Darwin’s notion of the survival of the fittest; both also show London’s avoidance of sentimentality and his commitment to presenting injustice and brutality. London married Bess Maddern, whom he claimed to have chosen for mating possibilities, not for love, in 1900. The couple had two daughters, Joan and Bess, and soon divorced. In 1905 London married Charmian Kittredge, his so-called “Mate Woman,” with whom he shared many of his adventures and who was the model for many of his female characters. Jack London died of uremia and renal colic in 1916.

The World of Jack London,

The Call of the Wild, and White Fang

1876 John Griffith London is born January 12 in San Francisco to Flora Wellman Chaney. Flora marries John London on September 7.

1878—1886 The Londons move around California as John looks for work on farms and ranches. Flora and John’s schemes to make money fail. In 1886 the Londons settle in Oakland, where young Jack works odd jobs and spends his free time in the Oakland Public Library reading novels and travelogues.

1891 London works in a cannery. He borrows money to buy a sloop, the Razzle-Dazzle, and sails through San Francisco Bay raiding oyster beds.

1892 London goes to work for the California Fish Patrol.

1893 A seven-month voyage aboard the sealing vessel Sophia Sutherland takes London to Hawaii, the Bonin Islands, Japan, and the Bering Sea. At sea, London begins to write, and his experiences inspire a piece of short fiction, “Story of a Typhoon off the Coast of Japan,” that wins first prize in a writing contest sponsored by the San Francisco Morning Call. The Panic of 1893 grips the country, and the growing use of machinery and the depressed economy lead to the unemployment of vast numbers of American workers.

1894 London joins Kelly’s Army, the western branch of a band of unemployed men known as Coxey’s Army, on a march to Washington, D.C., to protest economic conditions. He leaves the march before reaching Washington and makes his way north to Buffalo, New York, where he is arrested for vagrancy and spends a month in the Erie County Penitentiary. During his imprisonment, London formulates a social philosophy informed by the ideas of Karl Marx and Friedrich Nietzsche.

1895 London attends Oakland High School and publishes in school publications.

1896 London joins the Socialist Labor Party. He attends the University of California at Berkeley for one semester.

1897 London joins the Klondike Gold Rush and spends the winter in the Yukon.

1898 Upon returning from his unsuccessful Klondike trip, London devotes himself to writing.

1899 London sells his story “To the Man on the Trail,” one of many pieces that will appear in magazines and newspapers.

1900 London marries Bessie Mae Maddern. The Son of the Wolf, a collection of Klondike tales, is published.

1901 Joan, the London’s first daughter, is born January 15. The God of His Fathers, more stories about the Klondike, is published.

1902 London spends six weeks in the East End of London, accumulating material for his The People of the Abyss, a sociological study of the slums that is published in 1903. His second daughter, Becky, is born October 20. Children of the Frost, another collection of Klondike tales, is published.

1903 London falls in love with Charmian Kittredge; Bessie and Jack are separated. The Call of the Wild is published to worldwide acclaim.

1904 London covers the Russo-Japanese war as a Hearst correspondent. Bessie files for divorce.

1905 Kittredge and London are married. They purchase 129 acres in Glen Ellen, California, and name the spread “Beauty Ranch”; London uses the ranch to develop a scientific method of farming and to establish a breeding laboratory—ideas informed by his readings of Darwin. London travels through the Midwest and East on a Socialist lecture tour.

1906 London meets Sinclair Lewis at Yale. They subsequently correspond, and London buys a number of plot ideas from Lewis. London falls ill and returns to California, where he covers the San Francisco earthquake for Collier’s. He begins building a sailboat, the Snark, and plans a seven-year voyage around the world. Moon-Face and Other Stories and White Fang are published.

1907 Charmian and London sail the Snark from Oakland to Hawaii and the Marquesas Islands. Before Adam, a novel set in prehistoric times; Love of Life and Other Stories; and The Road, a biographical look at London’s days as a hobo, are published.

1908 London returns to Oakland briefly to deal with finances, then sails aboard the Snark to Tahiti, the Fiji Islands, the New Hebrides, and the Solomon Islands. In November he falls ill with multiple tropical diseases and is hospitalized in Australia. Iron Heel, a forward-looking novel about the perils of Fascism, is published.

1909 Charmian and Jack return to Oakland via Ecuador, Panama, and New Orleans. Martin Eden, a novel about a seaman who becomes a writer, is published.

1910 London begins plans for Wolf House, a mansion designed to last “a thousand years.” A child, Joy, dies two days after birth. Lost Face, a collection that includes the famous story “To Build a Fire”; Revolution and Other Essays, a collection of London’s thoughts on Socialism; Burning Daylight, a novel about the Klondike Gold Rush; and Theft, a play, are published.

1911 The Londons travel around California and Oregon. The Abysmal Brute, a novel about prizefighting and based on a plot purchased from Sinclair Lewis; When God Laughs and Other Stories; Adventure, a novel; and South Sea Tales are published.

1912 Jack and Charmian sail around Cape Horn aboard the Dirigio. Charmian miscarries again. The House of Pride and Other Tales of Hawaii; A Son of the Sun, another collection of South Sea tales; and Smoke Bellew, stories illustrated by Frederick Remington, are published.

1913 The Prohibition Party and other groups praise “John Barleycorn,” London’s astonishingly honest autobiographical treatise on alcoholism; others see this work as lacking in sincerity. Upton Sinclair noted, “That the work of a drinker who had no intention of stopping drinking should become a major propaganda piece in the campaign for Prohibition is

surely one of the choice ironies in the history of alcohol.” Fire destroys Wolf House.

1914 London covers the Mexican Revolution for Collier’s, but returns home after a severe attack of dysentery.

1915 London spends time in Hawaii hoping to improve his health. The Star Rover, a novel about reincarnation, is published.

1916 London resigns from the Socialist party in March because of its “loss of emphasis on class struggle.” He suffers sever bouts of uremia and rheumatism, and dies on November 22 of stroke and heart failure, which his physicians attribute to gastrointestinal uremia and renal colic.

Introduction

On July 25, 1897, twenty-one-year-old Jack London lit out for the territories and followed a herd of prospectors to the “new” Northland frontier in search of gold. By the time he reached the land of hope and lore, much of the gold had already been panned out of the tributaries of the Yukon River. After a year of following the well-worn trails from San Francisco to Seattle to Alaska to the Klondike region and back, London had gained little in the way of material wealth. He returned home in the summer of 1898 poorer than he was when he left, but he carried with him a store of information about life and landscape that he would mine for years to come; his memories and experiences would guarantee both his fame and his future fortune. In the frozen Arctic, London found confirmation for his philosophical leanings, especially his penchant toward Socialism and biological and social determinism. But his experiences also taught him the value of community, of the intense bonds that a confrontation with the wild can foster in humans and in animals.

The power of the wild and the love shared by human a

nd nonhuman are the subject of the texts brought together in this volume: The Call of the Wild (1903) and White Fang (1906). The Call of the Wild garnered Jack London immediate fame; it brought him commercial and artistic success and assured him a place in the American literary canon. Mention London’s name in a casual conversation and the unmediated, enthusiastic response is almost invariably the same: “I love The Call of the Wild!” This book, it seems, has come to symbolize much for many; but when asked to articulate further what makes for the lasting appeal of the book, many, like Buck, the novel’s canine protagonist, are unable to express their feelings. What, then, makes London’s often violent yet always poignant book so enduring?

London and the Klondike

By the time London boarded a steamer for his trip from San Francisco to Alaska, he had already led a colorful and dramatic life. He was a sloop owner and oyster pirate on San Francisco Bay and a deputy for the Fish Patrol at fifteen, a sailor traveling through the North and South Pacific hunting seals at seventeen, a coal-shoveler in a power plant, a Socialist, and a tramp at eighteen. By nineteen, a weary London saw himself, with others of the working classes, near “the bottom of the [Social] Pit... myself above them, not far, and hanging on to the slippery wall by main strength and sweat” (London, War of the Classes, pp. 274—275; see “For Further Reading”). Al ithough London was far from relinquishing his love of the active life, he feared being ruled by it. London fought in these early years to educate himself, and by that education to get himself out of the hard-laboring classes. As his hero informs his readers in the semi-autobiographical novel Martin Eden, writing offered a way to stoke the fires of both the body and the imagination, and so with characteristic determination, London set himself to the task of becoming a professional writer. By 1896, however, he realized that writing alone could not support a hungry family. The following year, London and his brother-in-law Captain James H. Shepard decided to try their luck panning for gold in the recently discovered strikes along the Yukon River in the Klondike.

The Son of the Wolf

The Son of the Wolf The Iron Heel

The Iron Heel Before Adam

Before Adam Smoke Bellew

Smoke Bellew The Call of the Wild

The Call of the Wild The Valley of the Moon Jack London

The Valley of the Moon Jack London Burning Daylight

Burning Daylight The Sea Wolf

The Sea Wolf White Fang

White Fang A Daughter of the Snows

A Daughter of the Snows The Night-Born

The Night-Born A Son Of The Sun

A Son Of The Sun Dutch Courage and Other Stories

Dutch Courage and Other Stories The People of the Abyss

The People of the Abyss Michael, Brother of Jerry

Michael, Brother of Jerry Love of Life, and Other Stories

Love of Life, and Other Stories Lost Face

Lost Face The Road

The Road Love of Life

Love of Life The Turtles of Tasman

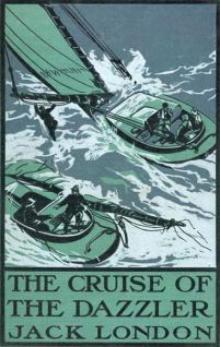

The Turtles of Tasman The Cruise of The Dazzler

The Cruise of The Dazzler The Heathen

The Heathen The Scab

The Scab The Faith of Men

The Faith of Men Adventure

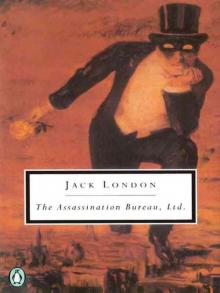

Adventure The Assassination Bureau, Ltd.

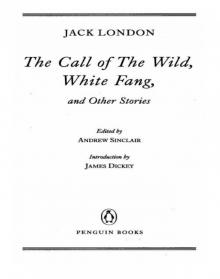

The Assassination Bureau, Ltd. The Call of the Wild, White Fang, and Other Stories

The Call of the Wild, White Fang, and Other Stories The Call of the Wild and Selected Stories

The Call of the Wild and Selected Stories Jerry of the Islands

Jerry of the Islands Hearts of Three

Hearts of Three The House of Pride

The House of Pride Moon-Face and Other Stories

Moon-Face and Other Stories Children of the Frost

Children of the Frost South Sea Tales

South Sea Tales The Strength of the Strong

The Strength of the Strong The Jacket (The Star-Rover)

The Jacket (The Star-Rover) The Little Lady of the Big House

The Little Lady of the Big House John Barleycorn

John Barleycorn ADaugter of Snows

ADaugter of Snows The Mutiny of the Elsinore

The Mutiny of the Elsinore Northland Stories

Northland Stories Tales of the Fish Patrol

Tales of the Fish Patrol Call of the Wild and White Fang (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Call of the Wild and White Fang (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Valley of the Moon

The Valley of the Moon The Cruise of the Snark

The Cruise of the Snark The Game

The Game An Autobiography of Jack London

An Autobiography of Jack London