- Home

- Jack London

The Faith of Men Page 5

The Faith of Men Read online

Page 5

“Sure,” Inwood said. “I saw it in the ’Frisco paper that came in over the ice this morning.”

“Well, and who’s the girl?” Pentfield demanded, somewhat with the air of patient fortitude with which one takes the bait of a catch and is aware at the time of the large laugh bound to follow at his expense.

Nick Inwood pulled the newspaper from his pocket and began looking it over, saying:-

“I haven’t a remarkable memory for names, but it seems to me it’s something like Mabel-Mabel-oh yes, here it-‘Mabel Holmes, daughter of Judge Holmes,’-whoever he is.”

Lawrence Pentfield never turned a hair, though he wondered how any man in the North could know her name. He glanced coolly from face to face to note any vagrant signs of the game that was being played upon him, but beyond a healthy curiosity the faces betrayed nothing. Then he turned to the gambler and said in cold, even tones:-

“Inwood, I’ve got an even five hundred here that says the print of what you have just said is not in that paper.”

The gambler looked at him in quizzical surprise. “Go ’way, child. I don’t want your money.”

“I thought so,” Pentfield sneered, returning to the game and laying a couple of bets.

Nick Inwood’s face flushed, and, as though doubting his senses, he ran careful eyes over the print of a quarter of a column. Then be turned on Lawrence Pentfield.

“Look here, Pentfield,” he said, in a quiet, nervous manner; “I can’t allow that, you know.”

“Allow what?” Pentfield demanded brutally.

“You implied that I lied.”

“Nothing of the sort,” came the reply. “I merely implied that you were trying to be clumsily witty.”

“Make your bets, gentlemen,” the dealer protested.

“But I tell you it’s true,” Nick Inwood insisted.

“And I have told you I’ve five hundred that says it’s not in that paper,” Pentfield answered, at the same time throwing a heavy sack of dust on the table.

“I am sorry to take your money,” was the retort, as Inwood thrust the newspaper into Pentfield’s hand.

Pentfield saw, though he could not quite bring himself to believe. Glancing through the headline, “Young Lochinvar came out of the North,” and skimming the article until the names of Mabel Holmes and Corry Hutchinson, coupled together, leaped squarely before his eyes, he turned to the top of the page. It was a San Francisco paper.

“The money’s yours, Inwood,” he remarked, with a short laugh. “There’s no telling what that partner of mine will do when he gets started.”

Then he returned to the article and read it word for word, very slowly and very carefully. He could no longer doubt. Beyond dispute, Corry Hutchinson had married Mabel Holmes. “One of the Bonanza kings,” it described him, “a partner with Lawrence Pentfield (whom San Francisco society has not yet forgotten), and interested with that gentleman in other rich, Klondike properties.” Further, and at the end, he read, “It is whispered that Mr. and Mrs. Hutchinson will, after a brief trip east to Detroit, make their real honeymoon journey into the fascinating Klondike country.”

“I’ll be back again; keep my place for me,” Pentfield said, rising to his feet and taking his sack, which meantime had hit the blower and came back lighter by five hundred dollars.

He went down the street and bought a Seattle paper. It contained the same facts, though somewhat condensed. Corry and Mabel were indubitably married. Pentfield returned to the Opera House and resumed his seat in the game. He asked to have the limit removed.

“Trying to get action,” Nick Inwood laughed, as he nodded assent to the dealer. “I was going down to the A. C. store, but now I guess I’ll stay and watch you do your worst.”

This Lawrence Pentfield did at the end of two hours’ plunging, when the dealer bit the end off a fresh cigar and struck a match as he announced that the bank was broken. Pentfield cashed in for forty thousand, shook hands with Nick Inwood, and stated that it was the last time he would ever play at his game or at anybody’s else’s.

No one knew nor guessed that he had been hit, much less hit hard. There was no apparent change in his manner. For a week he went about his work much as he had always done, when he read an account of the marriage in a Portland paper. Then he called in a friend to take charge of his mine and departed up the Yukon behind his dogs. He held to the Salt Water trail till White River was reached, into which he turned. Five days later he came upon a hunting camp of the White River Indians. In the evening there was a feast, and he sat in honour beside the chief; and next morning he headed his dogs back toward the Yukon. But he no longer travelled alone. A young squaw fed his dogs for him that night and helped to pitch camp. She had been mauled by a bear in her childhood and suffered from a slight limp. Her name was Lashka, and she was diffident at first with the strange white man that had come out of the Unknown, married her with scarcely a look or word, and now was carrying her back with him into the Unknown.

But Lashka’s was better fortune than falls to most Indian girls that mate with white men in the Northland. No sooner was Dawson reached than the barbaric marriage that had joined them was re-solemnized, in the white man’s fashion, before a priest. From Dawson, which to her was all a marvel and a dream, she was taken directly to the Bonanza claim and installed in the square-hewed cabin on the hill.

The nine days’ wonder that followed arose not so much out of the fact of the squaw whom Lawrence Pentfield had taken to bed and board as out of the ceremony that had legalized the tie. The properly sanctioned marriage was the one thing that passed the community’s comprehension. But no one bothered Pentfield about it. So long as a man’s vagaries did no special hurt to the community, the community let the man alone, nor was Pentfield barred from the cabins of men who possessed white wives. The marriage ceremony removed him from the status of squaw-man and placed him beyond moral reproach, though there were men that challenged his taste where women were concerned.

No more letters arrived from the outside. Six sledloads of mails had been lost at the Big Salmon. Besides, Pentfield knew that Corry and his bride must by that time have started in over the trail. They were even then on their honeymoon trip-the honeymoon trip he had dreamed of for himself through two dreary years. His lip curled with bitterness at the thought; but beyond being kinder to Lashka he gave no sign.

March had passed and April was nearing its end, when, one spring morning, Lashka asked permission to go down the creek several miles to Siwash Pete’s cabin. Pete’s wife, a Stewart River woman, had sent up word that something was wrong with her baby, and Lashka, who was pre-eminently a mother-woman and who held herself to be truly wise in the matter of infantile troubles, missed no opportunity of nursing the children of other women as yet more fortunate than she.

Pentfield harnessed his dogs, and with Lashka behind took the trail down the creek bed of Bonanza. Spring was in the air. The sharpness had gone out of the bite of the frost and though snow still covered the land, the murmur and trickling of water told that the iron grip of winter was relaxing. The bottom was dropping out of the trail, and here and there a new trail had been broken around open holes. At such a place, where there was not room for two sleds to pass, Pentfield heard the jingle of approaching bells and stopped his dogs.

A team of tired-looking dogs appeared around the narrow bend, followed by a heavily-loaded sled. At the gee-pole was a man who steered in a manner familiar to Pentfield, and behind the sled walked two women. His glance returned to the man at the gee-pole. It was Corry. Pentfield got on his feet and waited. He was glad that Lashka was with him. The meeting could not have come about better had it been planned, he thought. And as he waited he wondered what they would say, what they would be able to say. As for himself there was no need to say anything. The explaining was all on their side, and he was ready to listen to them.

As they drew in abreast, Corry recognized him and halted the dogs. With a “Hello, old man,” he held out his hand.

Pentfield shook it, but without warmth or speech. By this time the two women had come up, and he noticed that the second one was Dora Holmes. He doffed his fur cap, the flaps of which were flying, shook hands with her, and turned toward Mabel. She swayed forward, splendid and radiant, but faltered before his outstretched hand. He had intended to say, “How do you do, Mrs. Hutchinson?”-but somehow, the Mrs. Hutchinson had choked him, and all he had managed to articulate was the “How do you do?”

There was all the constraint and awkwardness in the situation he could have wished. Mabel betrayed the agitation appropriate to her position, while Dora, evidently brought along as some sort of peacemaker, was saying:-

“Why, what is the matter, Lawrence?”

Before he could answer, Corry plucked him by the sleeve and drew him aside.

“See here, old man, what’s this mean?” Corry demanded in a low tone, indicating Lashka with his eyes.

“I can hardly see, Corry, where you can have any concern in the matter,” Pentfield answered mockingly.

But Corry drove straight to the point.

“What is that squaw doing on your sled? A nasty job you’ve given me to explain all this away. I only hope it can be explained away. Who is she? Whose squaw is she?”

Then Lawrence Pentfield delivered his stroke, and he delivered it with a certain calm elation of spirit that seemed somewhat to compensate for the wrong that had been done him.

“She is my squaw,” he said; “Mrs. Pentfield, if you please.”

Corry Hutchinson gasped, and Pentfield left him and returned to the two women. Mabel, with a worried expression on her face, seemed holding herself aloof. He turned to Dora and asked, quite genially, as though all the world was sunshine:- “How did you stand the trip, anyway? Have any trouble to sleep warm?”

“And, how did Mrs. Hutchinson stand it?” he asked next, his eyes on Mabel.

“Oh, you dear ninny!” Dora cried, throwing her arms around him and hugging him. “Then you saw it, too! I thought something was the matter, you were acting so strangely.”

“I-I hardly understand,” he stammered.

“It was corrected in next day’s paper,” Dora chattered on. “We did not dream you would see it. All the other papers had it correctly, and of course that one miserable paper was the very one you saw!”

“Wait a moment! What do you mean?” Pentfield demanded, a sudden fear at his heart, for he felt himself on the verge of a great gulf.

But Dora swept volubly on.

“Why, when it became known that Mabel and I were going to Klondike, EveryOtherWeek said that when we were gone, it would be lovely on Myrdon Avenue, meaning, of course, lonely.”

“Then-”

“I am Mrs. Hutchinson,” Dora answered. “And you thought it was Mabel all the time-”

“Precisely the way of it,” Pentfield replied slowly. “But I can see now. The reporter got the names mixed. The Seattle and Portland paper copied.”

He stood silently for a minute. Mabel’s face was turned toward him again, and he could see the glow of expectancy in it. Corry was deeply interested in the ragged toe of one of his moccasins, while Dora was stealing sidelong glances at the immobile face of Lashka sitting on the sled. Lawrence Pentfield stared straight out before him into a dreary future, through the grey vistas of which he saw himself riding on a sled behind running dogs with lame Lashka by his side.

Then he spoke, quite simply, looking Mabel in the eyes.

“I am very sorry. I did not dream it. I thought you had married Corry. That is Mrs. Pentfield sitting on the sled over there.”

Mabel Holmes turned weakly toward her sister, as though all the fatigue of her great journey had suddenly descended on her. Dora caught her around the waist. Corry Hutchinson was still occupied with his moccasins. Pentfield glanced quickly from face to face, then turned to his sled.

“Can’t stop here all day, with Pete’s baby waiting,” he said to Lashka.

The long whip-lash hissed out, the dogs sprang against the breast bands, and the sled lurched and jerked ahead.

“Oh, I say, Corry,” Pentfield called back, “you’d better occupy the old cabin. It’s not been used for some time. I’ve built a new one on the hill.”

TOO MUCH GOLD

This being a story-and a truer one than it may appear-of a mining country, it is quite to be expected that it will be a hard-luck story. But that depends on the point of view. Hard luck is a mild way of terming it so far as Kink Mitchell and Hootchinoo Bill are concerned; and that they have a decided opinion on the subject is a matter of common knowledge in the Yukon country.

It was in the fall of 1896 that the two partners came down to the east bank of the Yukon, and drew a Peterborough canoe from a moss-covered cache. They were not particularly pleasant-looking objects. A summer’s prospecting, filled to repletion with hardship and rather empty of grub, had left their clothes in tatters and themselves worn and cadaverous. A nimbus of mosquitoes buzzed about each man’s head. Their faces were coated with blue clay. Each carried a lump of this damp clay, and, whenever it dried and fell from their faces, more was daubed on in its place. There was a querulous plaint in their voices, an irritability of movement and gesture, that told of broken sleep and a losing struggle with the little winged pests.

“Them skeeters’ll be the death of me yet,” Kink Mitchell whimpered, as the canoe felt the current on her nose, and leaped out from the bank.

“Cheer up, cheer up. We’re about done,” Hootchinoo Bill answered, with an attempted heartiness in his funereal tones that was ghastly. “We’ll be in Forty Mile in forty minutes, and then-cursed little devil!”

One hand left his paddle and landed on the back of his neck with a sharp slap. He put a fresh daub of clay on the injured part, swearing sulphurously the while. Kink Mitchell was not in the least amused. He merely improved the opportunity by putting a thicker coating of clay on his own neck.

They crossed the Yukon to its west bank, shot down-stream with easy stroke, and at the end of forty minutes swung in close to the left around the tail of an island. Forty Mile spread itself suddenly before them. Both men straightened their backs and gazed at the sight. They gazed long and carefully, drifting with the current, in their faces an expression of mingled surprise and consternation slowly gathering. Not a thread of smoke was rising from the hundreds of log-cabins. There was no sound of axes biting sharply into wood, of hammering and sawing. Neither dogs nor men loitered before the big store. No steamboats lay at the bank, no canoes, nor scows, nor poling-boats. The river was as bare of craft as the town was of life.

“Kind of looks like Gabriel’s tooted his little horn, and you an’ me has turned up missing,” remarked Hootchinoo Bill.

His remark was casual, as though there was nothing unusual about the occurrence. Kink Mitchell’s reply was just as casual as though he, too, were unaware of any strange perturbation of spirit.

“Looks as they was all Baptists, then, and took the boats to go by water,” was his contribution.

“My ol’ dad was a Baptist,” Hootchinoo Bill supplemented. “An’ he always did hold it was forty thousand miles nearer that way.”

This was the end of their levity. They ran the canoe in and climbed the high earth bank. A feeling of awe descended upon them as they walked the deserted streets. The sunlight streamed placidly over the town. A gentle wind tapped the halyards against the flagpole before the closed doors of the Caledonia Dance Hall. Mosquitoes buzzed, robins sang, and moose birds tripped hungrily among the cabins; but there was no human life nor sign of human life.

“I’m just dyin’ for a drink,” Hootchinoo Bill said and unconsciously his voice sank to a hoarse whisper.

His partner nodded his head, loth to hear his own voice break the stillness. They trudged on in uneasy silence till surprised by an open door. Above this door, and stretching the width of the building, a rude sign announced the same as the “ Monte Carlo.” But beside the door, hat over eyes, chair tilted back, a man sat

sunning himself. He was an old man. Beard and hair were long and white and patriarchal.

“If it ain’t ol’ Jim Cummings, turned up like us, too late for Resurrection!” said Kink Mitchell.

“Most like he didn’t hear Gabriel tootin’,” was Hootchinoo Bill’s suggestion.

“Hello, Jim! Wake up!” he shouted.

The old man unlimbered lamely, blinking his eyes and murmuring automatically: “What’ll ye have, gents? What’ll ye have?”

They followed him inside and ranged up against the long bar where of yore a half-dozen nimble bar-keepers found little time to loaf. The great room, ordinarily aroar with life, was still and gloomy as a tomb. There was no rattling of chips, no whirring of ivory balls. Roulette and faro tables were like gravestones under their canvas covers. No women’s voices drifted merrily from the dance-room behind. Ol’ Jim Cummings wiped a glass with palsied hands, and Kink Mitchell scrawled his initials on the dust-covered bar.

“Where’s the girls?” Hootchinoo Bill shouted, with affected geniality.

“Gone,” was the ancient bar-keeper’s reply, in a voice thin and aged as himself, and as unsteady as his hand.

“Where’s Bidwell and Barlow?”

“Gone.”

“And Sweetwater Charley?”

“Gone.”

“And his sister?”

“Gone too.”

“Your daughter Sally, then, and her little kid?”

“Gone, all gone.” The old man shook his head sadly, rummaging in an absent way among the dusty bottles.

“Great Sardanapolis! Where?” Kink Mitchell exploded, unable longer to restrain himself. “You don’t say you’ve had the plague?”

“Why, ain’t you heerd?” The old man chuckled quietly. “They-all’s gone to Dawson.”

“What-like is that?” Bill demanded. “A creek? or a bar? or a place?”

“Ain’t never heered of Dawson, eh?” The old man chuckled exasperatingly. “Why, Dawson ’s a town, a city, bigger’n Forty Mile. Yes, sir, bigger’n Forty Mile.”

The Son of the Wolf

The Son of the Wolf The Iron Heel

The Iron Heel Before Adam

Before Adam Smoke Bellew

Smoke Bellew The Call of the Wild

The Call of the Wild The Valley of the Moon Jack London

The Valley of the Moon Jack London Burning Daylight

Burning Daylight The Sea Wolf

The Sea Wolf White Fang

White Fang A Daughter of the Snows

A Daughter of the Snows The Night-Born

The Night-Born A Son Of The Sun

A Son Of The Sun Dutch Courage and Other Stories

Dutch Courage and Other Stories The People of the Abyss

The People of the Abyss Michael, Brother of Jerry

Michael, Brother of Jerry Love of Life, and Other Stories

Love of Life, and Other Stories Lost Face

Lost Face The Road

The Road Love of Life

Love of Life The Turtles of Tasman

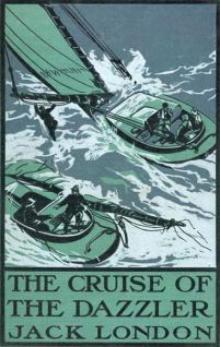

The Turtles of Tasman The Cruise of The Dazzler

The Cruise of The Dazzler The Heathen

The Heathen The Scab

The Scab The Faith of Men

The Faith of Men Adventure

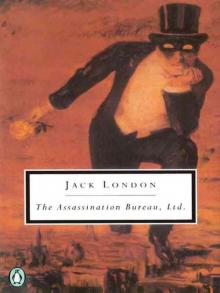

Adventure The Assassination Bureau, Ltd.

The Assassination Bureau, Ltd. The Call of the Wild, White Fang, and Other Stories

The Call of the Wild, White Fang, and Other Stories The Call of the Wild and Selected Stories

The Call of the Wild and Selected Stories Jerry of the Islands

Jerry of the Islands Hearts of Three

Hearts of Three The House of Pride

The House of Pride Moon-Face and Other Stories

Moon-Face and Other Stories Children of the Frost

Children of the Frost South Sea Tales

South Sea Tales The Strength of the Strong

The Strength of the Strong The Jacket (The Star-Rover)

The Jacket (The Star-Rover) The Little Lady of the Big House

The Little Lady of the Big House John Barleycorn

John Barleycorn ADaugter of Snows

ADaugter of Snows The Mutiny of the Elsinore

The Mutiny of the Elsinore Northland Stories

Northland Stories Tales of the Fish Patrol

Tales of the Fish Patrol Call of the Wild and White Fang (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Call of the Wild and White Fang (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Valley of the Moon

The Valley of the Moon The Cruise of the Snark

The Cruise of the Snark The Game

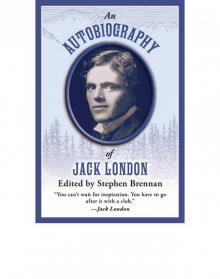

The Game An Autobiography of Jack London

An Autobiography of Jack London