- Home

- Jack London

The Call of the Wild and Selected Stories Page 21

The Call of the Wild and Selected Stories Read online

Page 21

Apparently young readers know, perhaps with a keenness special to their age, that the world is full of violence, both hidden and overt. Like the brothers Grimm, London tapped into a universally appealing narrative stream of timeless elements and character types—stories in far-off lands full of bellow and danger, peopled with villains and fools and allies at play in a world of hard realities, where the successful hero (always, of course, representing the child reader) finds a key to success, hard won. This tapping of elemental forces—forces that only unwelcome trouble and the gravest struggle can bring to the surface—is the same theme that makes comic book superheroes enter children’s imaginations so forcefully. The slowly dreamed, gradually unearthed wildness that Buck discovers inside himself is a magnetic, almost magical prowess that functions like the enhanced powers superheroes discover in themselves. After all, Buck can “break out” and pull a sled loaded with a thousand pounds. This is a superhero feat, a legendary moment. This slowly discovered strength—based on the will to survive, an experience of love, and the tapping of an atavistic wildness—provides the elemental key, the fundamental quality, the ancient wisdom that will unlock Buck’s “true” self and reveal its assets. And for this kind of discovery, terrible and dangerous struggle is required, along with the loss of the ordinary and cosseted life of ease in which Buck begins his life.

Children, of course, identify with animals (this does not cease when you grow up, though it is less often admitted). Kipling, Aesop’s fables, The Lion King—the many books and films for children that feature animal characters all attest to this. The elemental and “wild” forces within—anger, competition, jealousy, violent impulses, conflicts between love and selfish needs—are pictured as part of the external landscape in many of these tales. This wilderness both within and without is where The Call of the Wild takes place. It is aptly named, for perhaps we all wish to discover, or rediscover, within ourselves some bedrock quality capable of guiding us through the wilds, human and natural, of the world we inhabit.

In any case Buck’s wildness, emerging slowly throughout the narrative, is the real gold discovered in the book. It comes to mean that he fits with more and more ease and pleasure into the wild world of the Klondike. In the end he is completely at home and at one with the rhythms, ferocity and grandeur of the setting itself, in complete harmony with his world.

The book, which is one of London’s three best long works (The Call of the Wild, Martin Eden and The Sea-Wolf ) has a strong engine; it takes right off and does not stop till it reaches its destination, in a forward motion that is not unlike the forced travel as a sled dog that Buck has to endure. It is a combination adventure tale and psychological thriller, at once setting out a vividly described physical journey and a psychological, social, almost biological journey on Buck’s part. This journey takes him from a half-asleep and rather torpid civilized state through drastically tempering trials and finally into an almost tragic experience of love, loss and freedom. It is written in a muscular, often poetic prose that does not shy away from the hard, bitter or ugly but also has a lyric, spare musicality occasionally comparable to Kipling’s wonderful trance fables. Like Kipling’s, London’s writing enhances the book’s kinship with myth and parable.

London’s ability to write vivid, economical and concrete descriptions that launch the reader into an almost sensate experience of the story’s action is on full display here, as it is in “To Build a Fire” (where our fingers freeze and our hopes ebb right along with the doomed protagonist). The energy and speed with which London lodges you squarely in the snow, sends you into Buck’s hunger or fury or locates you in the almost maddening beauty of the springtime burgeoning cruelly around the starving sled dogs, make a kind of reading vertigo that tips you forward into the tale, full speed ahead. At his best, London’s ability to depict the natural world and its creatures in action is brilliant, and he is at his best here. London was describing a terrain and way of life he was intimately acquainted with, having spent a life-changing season in the Klondike himself, and he describes, with knife-edge vividness, a place whose physical settings and social realities deeply engaged him and made him, as he said, “think.”

The fact that the story combines the fascinations of a splendid travelogue and a narrative of both physical and psychological hardening makes it particularly appealing to children and young adults. All children face the necessity of schooling themselves to live within the social rules of their cultures, a hard task in which certain “primitive” and very intense emotions must be contained. Perhaps one of the deep appeals of this book is the glimpse it gives of a different, more atavistic set of parameters: the intuitive drives and dreams of the deep self London refers to when he writes about Buck’s dreaming by the fire, remembering and re-creating his alternative path. Buck’s life sets forth a basic struggle familiar to all children: the conflict between the comforts and niceties of civilization (where the rule is honor and forbearance) and the wilderness of the beast, within and without (where the rule is survival and cunning). And it gives this wilderness—the one within and the one without—its due, in all its splendor, scope and cost. Competition, dominance, jealousy, conflict—it’s all there, along with skill, cunning, strength and perseverance, the characteristics that serve to bring Buck into his own, both as sled dog leader and, eventually, as a wild creature returning to his wilderness home. In its guise as a story of transformation, the book tells a tale—germane to all of us, child and grown-up alike—of the journey in which we find our “true” or essential selves and mine our deepest capacities. A gold quite different from the one miners were seeking in the Klondike.

A central aspect of this book’s appeal is its idea of wildness. As a people inhabiting a very large country containing, at least until recently, large tracts of very sparsely populated land and with our history of pioneering and our strong romantic relationship to the idea of the wilderness as part of our national identity, Americans find the idea of wildness itself an electrifying theme. We have a notion of the wild’s beneficent effect on the character and the soul that has been carried forward in our literature and poetry to this day. How to relate to the vast spaces that exist beyond and apart from us and that turn us, like other creatures, back toward our animal natures is a constantly sounding undertow in The Call of the Wild. In fact, one deep question at the heart of this book is how to be the animals we are in a way that expresses our human natures, as Buck finds how to be the animal he is in a way that expresses his dog-wolf nature. This brings us to London’s meditations on competence. Like London’s The Sea-Wolf, although with a great deal less philosophizing, or like many of the stories in this volume, this book considers what it is to be a competent human being. It presents various scenarios of men competing for a place in the Alaskan wilderness, using the skills and wit that belong to them—or failing, catastrophically, to understand the realities of the wilderness and arriving unprepared for the rigors they will face, misusing the creatures and tools available to them. This can be fatal. (London himself barely survived his stint in the Klondike.)

The book is a paean to competence, both human and canine. The most vivid contrast here is between the threesome Hal, Charlie and Mercedes and John Thornton, all at one time Buck’s masters. The comic ineptitude of the caravan Hal, Charlie and Mercedes make up would be a charming and amusing set piece were it not for the brutal no-exit degradation of the dogs’ lives and the gathering sense of the doom that will come upon them all as the ill-prepared trio pursues various forms of silliness, bad judgment and ignorance in their trek. Like Dickens and Mark Twain, London is acutely aware of the underbelly of darkness in all that is bright and amusing. Through the beauties of the burgeoning springtime, lovingly described by London, the starving dogs and the self-involved and idiotic threesome move toward a fatal confrontation with the changing weather. Here, where the frozen rivers are highways, warmth can be as fatal as cold. Though London’s depiction of these three characters is spot-on and often funny, both Buck

and the reader know the same thing: we are headed for disaster. Just before Thornton’s intervention to keep Hal from beating Buck to death, Buck has lain down and given up partly because he recognizes intuitively that the fatal ineptitude of his present owners is reaching critical mass. When, in one of the book’s most vivid moments, the ice breaks and the whole caravan—the ill-fated dogs, the sled loaded with goods and their unregenerate owners—is swallowed up by the river, it is another proof of the implacability of survival’s rules.

In contrast, John Thornton is a man whose competence, as well as his ability to feel and honor real bonds, is a fulcrum for Buck’s growth and the expansion of his emotional and moral world. Thornton himself is able to negotiate the northern territory with almost as perfect a set of skills, as a human, as Buck develops as a dog. Dog and man make a complete partnership. The love between them teaches Buck something new and brings out in him a loyalty and a sense of devotion to something larger than himself that weights the civilized side of the internal battle he is undergoing between his wild and his domestic drives. But the gold that Thornton is seeking—and which he finds—is not the same ore that Buck finally finds within himself. Perhaps Thornton goes too far into the wild. Perhaps gold takes him where he should not go. In any case, his death (in a quintessentially nineteenth-century and non-PC event) releases Buck to answer the call and return to the wild.

When we are young, we love stories with well-defined beginnings, middles and ends. A clear arc to substantiate our own futures. As we grow older, we may grow more interested, by necessity or passion, in stories that break that mold and present the mix of things: the daily soup of past, present and future, where both time and the moral universe have become filled with shades of gray, and the arc seems less clear, the ride not quite the clear flight of arrow to target. But we can always return with pleasure to the classic flow that a story like The Call of the Wild presents, scary in its warnings, comforting in its clarities, and universally satisfying in its victories. Life, after all, does have a beginning, a middle and an end.

—Tobey Hiller

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Novels by Jack London

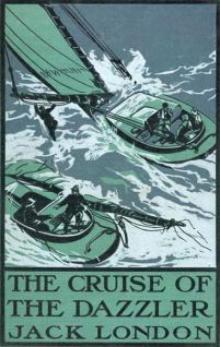

The Cruise of the Dazzler (1902)

A Daughter of the Snows (1902)

The Kempton-Wace Letters (1903)

The Call of the Wild (1903)

The Sea-Wolf (1904)

The Game (1905)

White Fang (1906)

Before Adam (1907)

The Iron Heel (1908)

Martin Eden (1909)

Burning Daylight (1910)

Adventure (1911)

The Abysmal Brute (1913)

The Valley of the Moon (1913)

The Mutiny of the Elsinore (1914)

The Scarlet Plague (1915)

The Star Rover (1915)

The Little Lady of the Big House (1916)

Jerry of the Islands (1917)

Michael, Brother of Jerry (1917)

Hearts of Three (1920)

The Assassination Bureau, Ltd. (completed by Robert L. Fish) (1963)

Anthologies

The Complete Short Stories of Jack London. 3 vols. Eds. Earle Labor, Robert C. Leitz, and Milo Shepard. Stanford, CA: Standford University Press, 1993.

Jack London on the Road: The Tramp Diary and Other Hobo Writings. Ed. Richard W. Etulain. Logan: Utah State University Press, 1979

Jack London Reports: War Correspondence, Sports Articles, and Miscellaneous Writings. Ed. King Hendricks and Irving Shepard. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1970.

The Portable Jack London. Ed. Earle Labor. New York: Penguin, 1994.

Biography and Criticism

Auerbach, Jonathan. Male Call: Becoming Jack London. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1996.

Cassuto, Leonard and Jeanne Campbell Reesman, eds. Reading Jack London. Stanford, CA: Standford University Press, 1996.

Hedrick, Joan D. Solitary Comrade: Jack London and His Work. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1982.

Hodson, Sara S., and Jeanne Reesman, eds. Jack London: 100 Years a Writer. San Marino, CA: Huntington Library Press, 2002

Johnston, Carolyn. Jack London: An American Radical. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1984.

Kershaw, Alex. Jack London: A Life. New York: St. Martin’s, 1998.

Kingman, Russ. Jack London: A Definitive Chronology. Middletown, CA: Rejl, 1992.

Labor, Earle and Jeanne Campbell Reesman. Jack London . Rev. ed. New York: Twayne, 1994.

London, Charmian. The Book of Jack London, 2 vols. New York: Century, 1921.

London, Joan. Jack London and His Daughters. Berke ley, CA: Heyday Books, 1990.

———. Jack London and His Times. New York: Doubleday, 1939.

Lundquist, James. Jack London: Adventures, Ideas and Fiction. New York: Ungar, 1987.

Nuernberg, Susan M., ed. The Critical Response to Jack London. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1995.

Perry, John. Jack London: An American Myth. Chicago: Nelson-Hall, 1981.

Schroeder, Alan. Jack London. New York: Chelsea House, 1992.

Stasz, Clarice. American Dreamers: Chairman and Jack London. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1988.

Tavernier-Courbin, Jacquline. The Call of the Wild: A Naturalistic Romance. New York: Twayne, 1994.

———, ed. Critical Essays on Jack London. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1983.

Walker, Franklin. Jack London and the Klondike: The Genesis of an American Writer. San Marino, CA: Huntington Library, 1966.

Watson, Charles N., Jr. The Novels of Jack London: A Reappraisal. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1983.

Wilcox, Earl J., ed. The Call of the Wild: A Casebook with Text. Chicago: Nelson-Hall, 1980.

The Son of the Wolf

The Son of the Wolf The Iron Heel

The Iron Heel Before Adam

Before Adam Smoke Bellew

Smoke Bellew The Call of the Wild

The Call of the Wild The Valley of the Moon Jack London

The Valley of the Moon Jack London Burning Daylight

Burning Daylight The Sea Wolf

The Sea Wolf White Fang

White Fang A Daughter of the Snows

A Daughter of the Snows The Night-Born

The Night-Born A Son Of The Sun

A Son Of The Sun Dutch Courage and Other Stories

Dutch Courage and Other Stories The People of the Abyss

The People of the Abyss Michael, Brother of Jerry

Michael, Brother of Jerry Love of Life, and Other Stories

Love of Life, and Other Stories Lost Face

Lost Face The Road

The Road Love of Life

Love of Life The Turtles of Tasman

The Turtles of Tasman The Cruise of The Dazzler

The Cruise of The Dazzler The Heathen

The Heathen The Scab

The Scab The Faith of Men

The Faith of Men Adventure

Adventure The Assassination Bureau, Ltd.

The Assassination Bureau, Ltd. The Call of the Wild, White Fang, and Other Stories

The Call of the Wild, White Fang, and Other Stories The Call of the Wild and Selected Stories

The Call of the Wild and Selected Stories Jerry of the Islands

Jerry of the Islands Hearts of Three

Hearts of Three The House of Pride

The House of Pride Moon-Face and Other Stories

Moon-Face and Other Stories Children of the Frost

Children of the Frost South Sea Tales

South Sea Tales The Strength of the Strong

The Strength of the Strong The Jacket (The Star-Rover)

The Jacket (The Star-Rover) The Little Lady of the Big House

The Little Lady of the Big House John Barleycorn

John Barleycorn ADaugter of Snows

ADaugter of Snows The Mutiny of the Elsinore

The Mutiny of the Elsinore Northland Stories

Northland Stories Tales of the Fish Patrol

Tales of the Fish Patrol Call of the Wild and White Fang (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Call of the Wild and White Fang (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Valley of the Moon

The Valley of the Moon The Cruise of the Snark

The Cruise of the Snark The Game

The Game An Autobiography of Jack London

An Autobiography of Jack London