- Home

- Jack London

The Scarlet Plague Page 2

The Scarlet Plague Read online

Page 2

II

THE old man showed pleasure in being thus called upon. He cleared histhroat and began.

"Twenty or thirty years ago my story was in great demand. But in thesedays nobody seems interested--"

"There you go!" Hare-Lip cried hotly. "Cut out the funny stuff and talksensible. What's _interested?_ You talk like a baby that don't knowhow."

"Let him alone," Edwin urged, "or he'll get mad and won't talk at all.Skip the funny places. We'll catch on to some of what he tells us."

"Let her go, Granser," Hoo-Hoo encouraged; for the old man was alreadymaundering about the disrespect for elders and the reversion to crueltyof all humans that fell from high culture to primitive conditions.

The tale began.

"There were very many people in the world in those days. San Franciscoalone held four millions--"

"What is millions?" Edwin interrupted.

Granser looked at him kindly.

"I know you cannot count beyond ten, so I will tell you. Hold up yourtwo hands. On both of them you have altogether ten fingers and thumbs.Very well. I now take this grain of sand--you hold it, Hoo-Hoo." Hedropped the grain of sand into the lad's palm and went on. "Now thatgrain of sand stands for the ten fingers of Edwin. I add another grain.That's ten more fingers. And I add another, and another, and another,until I have added as many grains as Edwin has fingers and thumbs. Thatmakes what I call one hundred. Remember that word--one hundred. Now Iput this pebble in Hare-Lip's hand. It stands for ten grains of sand, orten tens of fingers, or one hundred fingers. I put in ten pebbles. Theystand for a thousand fingers. I take a mussel-shell, and it stands forten pebbles, or one hundred grains of sand, or one thousand fingers...."And so on, laboriously, and with much reiteration, he strove to buildup in their minds a crude conception of numbers. As the quantitiesincreased, he had the boys holding different magnitudes in each oftheir hands. For still higher sums, he laid the symbols on the log ofdriftwood; and for symbols he was hard put, being compelled to use theteeth from the skulls for millions, and the crab-shells for billions.It was here that he stopped, for the boys were showing signs of becomingtired.

"There were four million people in San Francisco--four teeth."

The boys' eyes ranged along from the teeth and from hand to hand, downthrough the pebbles and sand-grains to Edwin's fingers. And back againthey ranged along the ascending series in the effort to grasp suchinconceivable numbers.

"That was a lot of folks, Granser," Edwin at last hazarded.

"Like sand on the beach here, like sand on the beach, each grain of sanda man, or woman, or child. Yes, my boy, all those people lived righthere in San Francisco. And at one time or another all those peoplecame out on this very beach--more people than there are grains of sand.More--more--more. And San Francisco was a noble city. And across thebay--where we camped last year, even more people lived, clear from PointRichmond, on the level ground and on the hills, all the way around toSan Leandro--one great city of seven million people.--Seven teeth...there, that's it, seven millions."

Again the boys' eyes ranged up and down from Edwin's fingers to theteeth on the log.

"The world was full of people. The census of 2010 gave eight billionsfor the whole world--eight crab-shells, yes, eight billions. It was notlike to-day. Mankind knew a great deal more about getting food. And themore food there was, the more people there were. In the year 1800, therewere one hundred and seventy millions in Europe alone. One hundred yearslater--a grain of sand, Hoo-Hoo--one hundred years later, at 1900, therewere five hundred millions in Europe--five grains of sand, Hoo-Hoo, andthis one tooth. This shows how easy was the getting of food, and how menincreased. And in the year 2000 there were fifteen hundred millionsin Europe. And it was the same all over the rest of the world. Eightcrab-shells there, yes, eight billion people were alive on the earthwhen the Scarlet Death began.

"I was a young man when the Plague came--twenty-seven years old; and Ilived on the other side of San Francisco Bay, in Berkeley. You rememberthose great stone houses, Edwin, when we came down the hills from ContraCosta? That was where I lived, in those stone houses. I was a professorof English literature."

I was a professor of English literature 054]

Much of this was over the heads of the boys, but they strove tocomprehend dimly this tale of the past.

"What was them stone houses for?" Hare-Lip queried.

"You remember when your dad taught you to swim?" The boy nodded."Well, in the University of California--that is the name we had forthe houses--we taught young men and women how to think, just as I havetaught you now, by sand and pebbles and shells, to know how many peoplelived in those days. There was very much to teach. The young men andwomen we taught were called students. We had large rooms in which wetaught. I talked to them, forty or fifty at a time, just as I am talkingto you now. I told them about the books other men had written beforetheir time, and even, sometimes, in their time--"

"Was that all you did?--just talk, talk, talk?" Hoo-Hoo demanded. "Whohunted your meat for you? and milked the goats? and caught the fish?"

"A sensible question, Hoo-Hoo, a sensible question. As I have told you,in those days food-getting was easy. We were very wise. A few men gotthe food for many men. The other men did other things. As you say, Italked. I talked all the time, and for this food was given me--muchfood, fine food, beautiful food, food that I have not tasted in sixtyyears and shall never taste again. I sometimes think the most wonderfulachievement of our tremendous civilization was food--its inconceivableabundance, its infinite variety, its marvellous delicacy. O mygrandsons, life was life in those days, when we had such wonderfulthings to eat."

This was beyond the boys, and they let it slip by, words and thoughts,as a mere senile wandering in the narrative.

"Our food-getters were called _freemen_. This was a joke. We of theruling classes owned all the land, all the machines, everything. Thesefood-getters were our slaves. We took almost all the food they got, andleft them a little so that they might eat, and work, and get us morefood--"

"I'd have gone into the forest and got food for myself," Hare-Lipannounced; "and if any man tried to take it away from me, I'd havekilled him."

The old man laughed.

"Did I not tell you that we of the ruling class owned all the land, allthe forest, everything? Any food-getter who would not get food for us,him we punished or compelled to starve to death. And very few did that.They preferred to get food for us, and make clothes for us, and prepareand administer to us a thousand--a mussel-shell, Hoo-Hoo--a thousandsatisfactions and delights. And I was Professor Smith in thosedays--Professor James Howard Smith. And my lecture courses were verypopular--that is, very many of the young men and women liked to hear metalk about the books other men had written.

"And I was very happy, and I had beautiful things to eat. And my handswere soft, because I did no work with them, and my body was cleanall over and dressed in the softest garments--

"He surveyed his mangy goat-skin with disgust.

"We did not wear such things in those days. Even the slaves had bettergarments. And we were most clean. We washed our faces and hands oftenevery day. You boys never wash unless you fall into the water or goswimming."

"Neither do you Granzer," Hoo-Hoo retorted.

"I know, I know, I am a filthy old man, but times have changed. Nobodywashes these days, there are no conveniences. It is sixty years since Ihave seen a piece of soap.

Sixty years since I have seen a piece of soap. 059]

"You do not know what soap is, and I shall not tell you, for I am tellingthe story of the Scarlet Death. You know what sickness is. We calledit a disease. Very many of the diseases came from what we called germs.Remember that word--germs. A germ is a very small thing. It is like awoodtick, such as you find on the dogs in the spring of the year whenthey run in the forest. Only the germ is very small. It is so small thatyou cannot see it--"

Hoo-Hoo began to laugh.

"You're a queer un, Granser, talking about

things you can't see. If youcan't see 'em, how do you know they are? That's what I want to know. Howdo you know anything you can't see?"

"A good question, a very good question, Hoo-Hoo. But we did see--some ofthem. We had what we called microscopes and ultramicroscopes, and we putthem to our eyes and looked through them, so that we saw things largerthan they really were, and many things we could not see without themicroscopes at all. Our best ultramicroscopes could make a germ lookforty thousand times larger. A mussel-shell is a thousand fingers likeEdwin's. Take forty mussel-shells, and by as many times larger was thegerm when we looked at it through a microscope. And after that, wehad other ways, by using what we called moving pictures, of making theforty-thousand-times germ many, many thousand times larger still. Andthus we saw all these things which our eyes of themselves could not see.Take a grain of sand. Break it into ten pieces. Take one piece and breakit into ten. Break one of those pieces into ten, and one of those intoten, and one of those into ten, and one of those into ten, and do it allday, and maybe, by sunset, you will have a piece as small as one of thegerms." The boys were openly incredulous. Hare-Lip sniffed and sneeredand Hoo-Hoo snickered, until Edwin nudged them to be silent.

"The woodtick sucks the blood of the dog, but the germ, being so verysmall, goes right into the blood of the body, and there it hasmany children. In those days there would be as many as a billion--acrab-shell, please--as many as that crab-shell in one man's body. Wecalled germs micro-organisms. When a few million, or a billion, of themwere in a man, in all the blood of a man, he was sick. These germs werea disease. There were many different kinds of them--more different kindsthan there are grains of sand on this beach. We knew only a few of thekinds. The micro-organic world was an invisible world, a world we couldnot see, and we knew very little about it. Yet we did know something.There was the _bacillus anthracis_; there was the _micrococcus_; therewas the _Bacterium termo_, and the _Bacterium lactis_--that's whatturns the goat milk sour even to this day, Hare-Lip; and there were_Schizomycetes_ without end. And there were many others...."

Here the old man launched into a disquisition on germs and theirnatures, using words and phrases of such extraordinary length andmeaninglessness, that the boys grinned at one another and looked outover the deserted ocean till they forgot the old man was babbling on.

"But the Scarlet Death, Granser," Edwin at last suggested.

Granser recollected himself, and with a start tore himself away from therostrum of the lecture-hall, where, to another world audience, hehad been expounding the latest theory, sixty years gone, of germs andgerm-diseases.

"Yes, yes, Edwin; I had forgotten. Sometimes the memory of the past isvery strong upon me, and I forget that I am a dirty old man, clad ingoat-skin, wandering with my savage grandsons who are goatherds inthe primeval wilderness. 'The fleeting systems lapse like foam,' and solapsed our glorious, colossal civilization. I am Granser, a tired oldman. I belong to the tribe of Santa Rosans. I married into that tribe.My sons and daughters married into the Chauffeurs, the Sacramen-tos, andthe Palo-Altos. You, Hare-Lip, are of the Chauffeurs. You, Edwin, areof the Sacramentos. And you, Hoo-Hoo, are of the Palo-Altos. Your tribetakes its name from a town that was near the seat of another greatinstitution of learning. It was called Stanford University. Yes, Iremember now. It is perfectly clear. I was telling you of the ScarletDeath. Where was I in my story?"

"You was telling about germs, the things you can't see but which makemen sick," Edwin prompted.

"Yes, that's where I was. A man did not notice at first when only a fewof these germs got into his body. But each germ broke in half and becametwo germs, and they kept doing this very rapidly so that in a short timethere were many millions of them in the body. Then the man was sick. Hehad a disease, and the disease was named after the kind of a germ thatwas in him. It might be measles, it might be influenza, it might beyellow fever; it might be any of thousands and thousands of kinds ofdiseases.

"Now this is the strange thing about these germs. There were always newones coming to live in men's bodies. Long and long and long ago, whenthere were only a few men in the world, there were few diseases. Butas men increased and lived closely together in great cities andcivilizations, new diseases arose, new kinds of germs entered theirbodies. Thus were countless millions and billions of human beingskilled. And the more thickly men packed together, the more terrible werethe new diseases that came to be. Long before my time, in the middleages, there was the Black Plague that swept across Europe. It sweptacross Europe many times. There was tuberculosis, that entered into menwherever they were thickly packed. A hundred years before my time therewas the bubonic plague. And in Africa was the sleeping sickness. Thebacteriologists fought all these sicknesses and destroyed them, just asyou boys fight the wolves away from your goats, or squash the mosquitoesthat light on you. The bacteriologists--"

"But, Granser, what is a what-you-call-it?" Edwin interrupted.

"You, Edwin, are a goatherd. Your task is to watch the goats. You know agreat deal about goats. A bacteriologist watches germs. That's histask, and he knows a great deal about them. So, as I was saying, thebacteriologists fought with the germs and destroyed them--sometimes.There was leprosy, a horrible disease. A hundred years before I wasborn, the bacteriologists discovered the germ of leprosy. They knew allabout it. They made pictures of it. I have seen those pictures. Butthey never found a way to kill it. But in 1984, there was the PantoblastPlague, a disease that broke out in a country called Brazil and thatkilled millions of people. But the bacteriologists found it out, andfound the way to kill it, so that the Pantoblast Plague went no farther.They made what they called a serum, which they put into a man's body andwhich killed the pantoblast germs without killing the man. And in 1910,there was Pellagra, and also the hookworm. These were easily killedby the bacteriologists. But in 1947 there arose a new disease that hadnever been seen before. It got into the bodies of babies of only tenmonths old or less, and it made them unable to move their hands andfeet, or to eat, or anything; and the bacteriologists were eleven yearsin discovering how to kill that particular germ and save the babies.

"In spite of all these diseases, and of all the new ones that continuedto arise, there were more and more men in the world. This was because itwas easy to get food. The easier it was to get food, the more menthere were; the more men there were, the more thickly were they packedtogether on the earth; and the more thickly they were packed, the morenew kinds of germs became diseases. There were warnings. Soldervetzsky,as early as 1929, told the bacteriologists that they had no guarantyagainst some new disease, a thousand times more deadly than any theyknew, arising and killing by the hundreds of millions and even by thebillion. You see, the micro-organic world remained a mystery to the end.They knew there was such a world, and that from time to time armies ofnew germs emerged from it to kill men.

"And that was all they knew about it. For all they knew, in thatinvisible micro-organic world there might be as many different kinds ofgerms as there are grains of sand on this beach. And also, in that sameinvisible world it might well be that new kinds of germs came to be.It might be there that life originated--the 'abysmal fecundity,'Soldervetzsky called it, applying the words of other men who had writtenbefore him...."

It was at this point that Hare-Lip rose to his feet, an expression ofhuge contempt on his face.

Granser, you make me sick with your gabble 071]

"Granser," he announced, "you make me sick with your gabble. Why don'tyou tell about the Red Death? If you ain't going to, say so, an' we'llstart back for camp."

The old man looked at him and silently began to cry. The weak tears ofage rolled down his cheeks and all the feebleness of his eighty-sevenyears showed in his grief-stricken countenance.

"Sit down," Edwin counselled soothingly. "Granser's all right. He's justgettin' to the Scarlet Death, ain't you, Granser? He's just goin' totell us about it right now. Sit down, Hare-Lip. Go ahead, Granser."

The Son of the Wolf

The Son of the Wolf The Iron Heel

The Iron Heel Before Adam

Before Adam Smoke Bellew

Smoke Bellew The Call of the Wild

The Call of the Wild The Valley of the Moon Jack London

The Valley of the Moon Jack London Burning Daylight

Burning Daylight The Sea Wolf

The Sea Wolf White Fang

White Fang A Daughter of the Snows

A Daughter of the Snows The Night-Born

The Night-Born A Son Of The Sun

A Son Of The Sun Dutch Courage and Other Stories

Dutch Courage and Other Stories The People of the Abyss

The People of the Abyss Michael, Brother of Jerry

Michael, Brother of Jerry Love of Life, and Other Stories

Love of Life, and Other Stories Lost Face

Lost Face The Road

The Road Love of Life

Love of Life The Turtles of Tasman

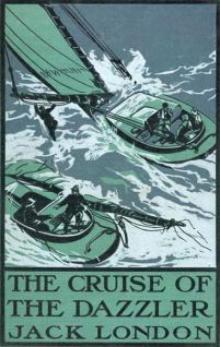

The Turtles of Tasman The Cruise of The Dazzler

The Cruise of The Dazzler The Heathen

The Heathen The Scab

The Scab The Faith of Men

The Faith of Men Adventure

Adventure The Assassination Bureau, Ltd.

The Assassination Bureau, Ltd. The Call of the Wild, White Fang, and Other Stories

The Call of the Wild, White Fang, and Other Stories The Call of the Wild and Selected Stories

The Call of the Wild and Selected Stories Jerry of the Islands

Jerry of the Islands Hearts of Three

Hearts of Three The House of Pride

The House of Pride Moon-Face and Other Stories

Moon-Face and Other Stories Children of the Frost

Children of the Frost South Sea Tales

South Sea Tales The Strength of the Strong

The Strength of the Strong The Jacket (The Star-Rover)

The Jacket (The Star-Rover) The Little Lady of the Big House

The Little Lady of the Big House John Barleycorn

John Barleycorn ADaugter of Snows

ADaugter of Snows The Mutiny of the Elsinore

The Mutiny of the Elsinore Northland Stories

Northland Stories Tales of the Fish Patrol

Tales of the Fish Patrol Call of the Wild and White Fang (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Call of the Wild and White Fang (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Valley of the Moon

The Valley of the Moon The Cruise of the Snark

The Cruise of the Snark The Game

The Game An Autobiography of Jack London

An Autobiography of Jack London