- Home

- Jack London

The Scab Page 2

The Scab Read online

Page 2

In this connection, and as one of many walking delegates for the nations, M. Leroy-Beaulieu, the noted French economist, may well be quoted. In a letter to the Vienna Tageblatt, he advocates an economic alliance among the Continental nations for the purpose of barring out American goods, an economic alliance, in his own language, "which may possibly and desirably develop into a political alliance."

It will be noted in the utterances of the Continental walking delegates that, one and all, they leave England out of the proposed union. And in England herself the feeling is growing that her days are numbered if she cannot unite for offense and defense with the great American Scab. As Andrew Carnegie said some time ago, "The only course for Great Britain seems to be reunion with her grandchild, or sure decline to a secondary place, and then to comparative insignificance in the future annals of the English-speaking race."

Cecil Rhodes, speaking of what would have obtained but for the pig-headedness of George III., and of what will obtain when England and the United States are united, said, "No cannon would . . . be fired on either hemisphere but by permission of the English race." It would seem that England, fronted by the hostile Continental Union and flanked by the great American Scab, has nothing left but to join with the Scab and play the historic labor-rôle of armed Pinkerton. Granting the words of Cecil Rhodes, the United States would be enabled to scab without let or hindrance on Europe, while England, as professional strike-breaker and policeman, destroyed the unions and kept order.

All this may appear fantastic and erroneous, but there is in it a soul of truth vastly more significant than it may seem. Civilization may be expressed to-day in terms of trade unionism. Individual struggles have largely passed away, but group struggles increase prodigiously. And the things for which the groups struggle are the same as of old. Shorn of all subtleties and complexities, the chief struggle of men, and of groups of men, is for food and shelter. And, as of old they struggled with tooth and nail, so to-day they struggle, with teeth and nails elongated into armies and navies, machines, and economic advantages.

Under the definition that a scab is one who gives more value for the same price than another, it would seem that society can be generally divided into the two classes of the scabs and the nonscabs. But on closer investigation, however, it will be seen that the non-scab is almost a vanishing quantity. In the social jungle everybody is preying upon everybody else. As in the case of Mr. Rockefeller, he who was a scab yesterday is a non-scab to-day, and to-morrow may be a scab again.

The woman stenographer or bookkeeper who receives forty dollars per month where a man was receiving seventy-five is a scab. So is the woman who does a man's work at a weaving machine, and the child who goes into the mill or factory. And the father, who is scabbed out of work by the wives and children of other men, sends his own wife and children to scab in order to save himself.

When a publisher offers an author better royalties than other publishers have been paying him, he is scabbing on those other publishers. The reporter on a newspaper who feels he should be receiving a larger salary for his work, says so, and is shown the door, is replaced by a reporter who is a scab; whereupon, when the belly-need presses, the displaced reporter goes to another paper and scabs himself. The minister who hardens his heart to a call, and waits for a certain congregation to offer him say five hundred a year more, often finds himself scabbed upon by another and more impecunious minister; and the next time it is his turn to scab while a brother minister is hardening his heart to a call. The scab is everywhere. The professional strike-breakers, who, as a class, receive large wages, will scab on one another, while scab unions are even formed to prevent scabbing upon scabs.

There are non-scabs, but they are usually born so, and are protected by the whole might of society in the possession of their food and shelter. King Edward is such a type, as are all individuals who receive hereditary food-and-shelter privileges, such as the present Duke of Bedford, for instance, who yearly receives $75,000 from the good people of London because some former king gave some former ancestor of his the market privileges of Covent Garden. The irresponsible rich are likewise non-scabs, and by them is meant that coupon-clipping class which hires its managers and brains to invest the money usually left it by its ancestors.

Outside these lucky creatures, all the rest, at one time or another in their lives, are scabs, at one time or another are engaged in giving more for a certain price than any one else. The meek professor in some endowed institution, by his meek suppression of his convictions, is giving more for his salary than the other more outspoken professor gave, whose chair he occupies. And when a political party dangles a full dinner-pail in the eyes of the toiling masses, it is offering more for a vote than the dubious dollar of the opposing party. Even a money-lender is not above taking a slightly lower rate of interest and saying nothing about it.

Such is the tangle of conflicting interests in a tooth-and-nail society that people cannot avoid being scabs, are often made so against their desires, and unconsciously. When several trades in a certain locality demand and receive an advance in wages, they are unwittingly making scabs of their fellow laborers in that district who have received no advance in wages. In San Francisco the barbers, laundry workers, and milk-wagon drivers received such an advance in wages. Their employers promptly added the amount of this advance to the selling price of their wares. The price of shaves, of washing, and of milk went up. This reduced the purchasing power of the unorganized laborers, and, in point of fact, reduced their wages and made them greater scabs.

Because the British laborer is disinclined to scab, that is, because he restricts his output in order to give less for the wage he receives, it is to a certain extent made possible for the American capitalist, who receives a less restricted output from his laborers, to play the scab on the English capitalist. As a result of this (of course, combined with other causes), the American capitalist and the American laborer are striking at the food and shelter of the English capitalist and laborer.

The English laborer is starving to-day because, among other things, he is not a scab. He practices the policy of "Ca' Canny," which may be defined as "go easy." In order to get most for least, in many trades he performs but from one fourth to one sixth of the labor he is well able to perform. An instance of this is found in the building of the Westinghouse Electric Works at Manchester. The British limit per man was 400 bricks per day. The Westinghouse Company imported a "driving" American contractor aided by half-a-dozen "driving" American foremen, and the British bricklayer swiftly attained an average of 1800 bricks per day, with a maximum of 2500 bricks for the plainest work.

But the British laborer's policy of Ca' Canny, which is the very honorable one of giving least for most, and which is likewise the policy of the English capitalist, is nevertheless frowned upon by the English capitalist whose business existence is threatened by the great American Scab. From the rise of the factory system, the English capitalist gladly embraced the opportunity, wherever he found it, of giving least for most. He did it all over the world wherever he enjoyed a market monopoly, and he did it at home, with the laborers employed in his mills, destroying them like flies till prevented, within limits, by the passage of the Factory Acts. Some of the proudest fortunes of England to-day may trace their origin to the giving of least for most to the miserable slaves of the factory towns. But at the present time the English capitalist is outraged because his laborers are employing against him precisely the same policy he employed against them, and which he would employ again did the chance present itself.

Yet Ca' Canny is a disastrous thing to the British laborer. It has driven ship-building from England to Scotland, bottle-making from Scotland to Belgium, flint-glass-making from England to Germany, and to-day it is steadily driving industry after industry to other countries. A correspondent from Northampton wrote not long ago: "Factories are working half and third time.... There is no strike, there is no real labor trouble, but the masters and men are alike suffering from she

er lack of employment. Markets which were once theirs are now American." It would seem that the unfortunate British laborer is 'twixt the devil and the deep sea. If he gives most for least, he faces a frightful slavery such as marked the beginning of the factory system. If he gives least for most, he drives industry away to other countries, and has no work at all.

But the union laborers of the United States have nothing to boast of, while, according to their trade-union ethics, they have a great deal of which to be ashamed. They passionately preach short hours and big wages, the shorter the hours and the bigger the wages the better. Their hatred for a scab is as terrible as the hatred of a patriot for a traitor, of a Christian for a Judas. And in the face of all this they are as colossal scabs as the United States is a colossal scab. For all of their boasted unions and high labor-ideals, they are about the most thorough-going scabs on the planet.

Receiving $4.50 per day, because of his proficiency and immense working power, the American laborer has been known to scab upon scabs (so called) who took his place and received only $.90 per day for a longer day. In this particular instance, five Chinese coolies, working longer hours, gave less value for the price received from their employer than did one American laborer.

It is upon his brother laborers overseas that the American laborer most outrageously scabs. As Mr. Casson has shown, an English nailmaker gets $3.00 per week, while an American nailmaker gets $30.00. But the English worker turns out 200 pounds of nails per week, while the American turns out 5500 pounds. If he were as "fair" as his English brother, other things being equal, he would be receiving, at the English worker's rate of pay, $82.50. As it is, he is scabbing upon his English brother to the tune of $79.50 per week. Dr. Schultze-Gaevernitz has shown that a German weaver produces 466 yards of cotton a week at a cost of .303 per yard, while an American weaver produces 1200 yards at a cost of .02 per yard.

But, it may be objected, a great part of this is due to the more improved American machinery. Very true; but, none the less, a great part is still due to the superior energy, skill, and willingness of the American laborer. The English laborer is faithful to the policy of Ca' Canny. He refuses point blank to get the work out of a machine that the New World scab gets out of a machine. Mr. Maxim, observing a wasteful hand-labor process in his English factory, invented a machine which he proved capable of displacing several men. But workman after workman was put at the machine, and without exception they turned out neither more nor less than a workman turned out by hand. They obeyed the mandate of the union and went easy, while Mr. Maxim gave up in despair. Nor will the British workman run machines at as high speed as the American, nor will he run so many. An American workman will "give equal attention simultaneously to three, four, or six machines or tools, while the British workman is compelled by his trade union to limit his attention to one, so that employment may be given to half-a-dozen men."

But to scabbing, no blame attaches itself anywhere. All the world is a scab, and, with rare exceptions, all the people in it are scabs. The strong, capable workman gets a job and holds it because of his strength and capacity. And he holds it because out of his strength and capacity he gives a better value for his wage than does the weaker and less capable workman. Therefore he is scabbing upon his weaker and less capable brother workman. This is incontrovertible. He is giving more value for the price paid by the employer.

The superior workman scabs upon the inferior workman because he is so constituted and cannot help it. The one, by fortune of birth and upbringing, is strong and capable; the other, by fortune of birth and upbringing, is not so strong or capable. It is for the same reason that one country scabs upon another. That country which has the good fortune to possess great natural resources, a finer sun and soil, unhampering institutions, and a deft and intelligent labor class and capitalist class, is bound to scab upon a country less fortunately situated. It is the good fortune of the United States that is making her the colossal scab, just as it is the good fortune of one man to be born with a straight back while his brother is born with a hump.

It is not good to give most for least, not good to be a scab. The word has gained universal opprobrium. On the other hand, to be a non-scab, to give least for most, is universally branded as stingy, selfish, and unchristian-like. So all the world, like the British workman, is 'twixt the devil and the deep sea. It is treason to one's fellows to scab, it is treason to God and unchristian-like not to scab.

Since to give least for most and to give most for least are universally bad, what remains? Equity remains, which is to give like for like, the same for the same, neither more nor less. But this equity, society, as at present constituted, cannot give. It is not in the nature of present-day society for men to give like for like, the same for the same. And as long as men continue to live in this competitive society, struggling tooth and nail with one another for food and shelter, (which is to struggle tooth and nail with one another for life), that long will the scab continue to exist. His will to live will force him to exist. He may be flouted and jeered by his brothers, he may be beaten with bricks and clubs by the men who by superior strength and capacity scab upon him as he scabs upon them by longer hours and smaller wages, but through it all he will persist, going them one better, and giving a bit more of most for least than they are giving.

Jack London.

[1] The Social Unrest. New York: The Macmillan Co. 1903.

The Son of the Wolf

The Son of the Wolf The Iron Heel

The Iron Heel Before Adam

Before Adam Smoke Bellew

Smoke Bellew The Call of the Wild

The Call of the Wild The Valley of the Moon Jack London

The Valley of the Moon Jack London Burning Daylight

Burning Daylight The Sea Wolf

The Sea Wolf White Fang

White Fang A Daughter of the Snows

A Daughter of the Snows The Night-Born

The Night-Born A Son Of The Sun

A Son Of The Sun Dutch Courage and Other Stories

Dutch Courage and Other Stories The People of the Abyss

The People of the Abyss Michael, Brother of Jerry

Michael, Brother of Jerry Love of Life, and Other Stories

Love of Life, and Other Stories Lost Face

Lost Face The Road

The Road Love of Life

Love of Life The Turtles of Tasman

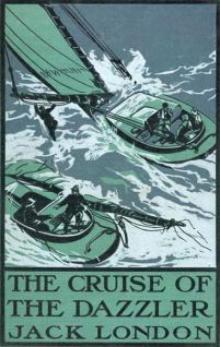

The Turtles of Tasman The Cruise of The Dazzler

The Cruise of The Dazzler The Heathen

The Heathen The Scab

The Scab The Faith of Men

The Faith of Men Adventure

Adventure The Assassination Bureau, Ltd.

The Assassination Bureau, Ltd. The Call of the Wild, White Fang, and Other Stories

The Call of the Wild, White Fang, and Other Stories The Call of the Wild and Selected Stories

The Call of the Wild and Selected Stories Jerry of the Islands

Jerry of the Islands Hearts of Three

Hearts of Three The House of Pride

The House of Pride Moon-Face and Other Stories

Moon-Face and Other Stories Children of the Frost

Children of the Frost South Sea Tales

South Sea Tales The Strength of the Strong

The Strength of the Strong The Jacket (The Star-Rover)

The Jacket (The Star-Rover) The Little Lady of the Big House

The Little Lady of the Big House John Barleycorn

John Barleycorn ADaugter of Snows

ADaugter of Snows The Mutiny of the Elsinore

The Mutiny of the Elsinore Northland Stories

Northland Stories Tales of the Fish Patrol

Tales of the Fish Patrol Call of the Wild and White Fang (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Call of the Wild and White Fang (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Valley of the Moon

The Valley of the Moon The Cruise of the Snark

The Cruise of the Snark The Game

The Game An Autobiography of Jack London

An Autobiography of Jack London