- Home

- Jack London

Moon-Face and Other Stories Page 2

Moon-Face and Other Stories Read online

Page 2

“But I saw it through the hole in the canvas. De Ville drew his handkerchief from his pocket, made as though to mop the sweat from his face with it (it was a hot day), and at the same time walked past Wallace’s back. The look troubled me at the time, for not only did I see hatred in it, but I saw triumph as well.

“‘De Ville will bear watching,’ I said to myself, and I really breathed easier when I saw him go out the entrance to the circus grounds and board an electric car for down town. A few minutes later I was in the big tent, where I had overhauled Red Denny. King Wallace was doing his turn and holding the audience spellbound. He was in a particularly vicious mood, and he kept the lions stirred up till they were all snarling, that is, all of them except old Augustus, and he was just too fat and lazy and old to get stirred up over anything.

“Finally Wallace cracked the old lion’s knees with his whip and got him into position. Old Augustus, blinking good-naturedly, opened his mouth and in popped Wallace’s head. Then the jaws came together, CRUNCH, just like that.”

The Leopard Man smiled in a sweetly wistful fashion, and the faraway look came into his eyes.

“And that was the end of King Wallace,” he went on in his sad, low voice. “After the excitement cooled down I watched my chance and bent over and smelled Wallace’s head. Then I sneezed.”

“It … it was …?” I queried with halting eagerness.

“Snuff—that De Ville dropped on his hair in the dressing tent. Old Augustus never meant to do it. He only sneezed.”

LOCAL COLOR

“I DO not see why you should not turn this immense amount of unusual information to account,” I told him. “Unlike most men equipped with similar knowledge, YOU have expression. Your style is—”

“Is sufficiently—er—journalese?” he interrupted suavely.

“Precisely! You could turn a pretty penny.”

But he interlocked his fingers meditatively, shrugged his shoulders, and dismissed the subject.

“I trave tried it. It does not pay.”

“It was paid for and published,” he added, after a pause. “And I was also honored with sixty days in the Hobo.”

“The Hobo?” I ventured.

“The Hobo—” He fixed his eyes on my Spencer and ran along the titles while he cast his definition. “The Hobo, my dear fellow, is the name for that particular place of detention in city and county jails wherein are assembled tramps, drunks, beggars, and the riff-raff of petty offenders. The word itself is a pretty one, and it has a history. Hautbois—there’s the French of it. haut, meaning high, and bois, wood. In English it becomes hautboy, a wooden musical instrument of two-foot tone, I believe, played with a double reed, an oboe, in fact. You remember in ‘Henry IV’—

“‘The case of a treble hautboy Was a mansion for him, a court.’

From this to ho-boy is but a step, and for that matter the English used the terms interchangeably. But—and mark you, the leap paralyzes one—crossing the Western Ocean, in New York City, hautboy, or ho-boy, becomes the name by which the night-scavenger is known. In a way one understands its being born of the contempt for wandering players and musical fellows. But see the beauty of it! the burn and the brand! The night-scavenger, the pariah, the miserable, the despised, the man without caste! And in its next incarnation, consistently and logically, it attaches itself to the American outcast, namely, the tramp. Then, as others have mutilated its sense, the tramp mutilates its form, and ho-boy becomes exultantly hobo. Wherefore, the large stone and brick cells, lined with double and triple-tiered bunks, in which the Law is wont to incarcerate him, he calls the Hobo. Interesting, isn’t it?”

And I sat back and marvelled secretly at this encyclopaedic-minded man, this Leith Clay-Randolph, this common tramp who made himself at home in my den, charmed such friends as gathered at my small table, outshone me with his brilliance and his manners, spent my spending money, smoked my best cigars, and selected from my ties and studs with a cultivated and discriminating eye.

He absently walked over to the shelves and looked into Loria’s “Economic Foundation of Society.”

“I like to talk with you,” he remarked. “You are not indifferently schooled. You’ve read the books, and your economic interpretation of history, as you choose to call it” (this with a sneer), “eminently fits you for an intellectual outlook on life. But your sociologic judgments are vitiated by your lack of practical knowledge. Now I, who know the books, pardon me, somewhat better than you, know life, too. I have lived it, naked, taken it up in both my hands and looked at it, and tasted it, the flesh and the blood of it, and, being purely an intellectual, I have been biased by neither passion nor prejudice. All of which is necessary for clear concepts, and all of which you lack. Ah! a really clever passage. Listen!”

And he read aloud to me in his remarkable style, paralleling the text with a running criticism and commentary, lucidly wording involved and lumbering periods, casting side and cross lights upon the subject, introducing points the author had blundered past and objections he had ignored, catching up lost ends, flinging a contrast into a paradox and reducing it to a coherent and succinctly stated truth—in short, flashing his luminous genius in a blaze of fire over pages erstwhile dull and heavy and lifeless.

It is long since that Leith Clay-Randolph (note the hyphenated surname) knocked at the back door of Idlewild and melted the heart of Gunda. Now Gunda was cold as her Norway hills, though in her least frigid moods she was capable of permitting especially nice-looking tramps to sit on the back stoop and devour lone crusts and forlorn and forsaken chops. But that a tatterdemalion out of the night should invade the sanctity of her kitchen-kingdom and delay dinner while she set a place for him in the warmest corner, was a matter of such moment that the Sunflower went to see. Ah, the Sunflower, of the soft heart and swift sympathy! Leith Clay-Randolph threw his glamour over her for fifteen long minutes, whilst I brooded with my cigar, and then she fluttered back with vague words and the suggestion of a cast-off suit I would never miss.

“Surely I shall never miss it,” I said, and I had in mind the dark gray suit with the pockets draggled from the freightage of many books—books that had spoiled more than one day’s fishing sport.

“I should advise you, however,” I added, “to mend the pockets first.”

But the Sunflower’s face clouded. “N—o,” she said, “the black one.”

“The black one!” This explosively, incredulously. “I wear it quite often. I—I intended wearing it tonight.”

“You have two better ones, and you know I never liked it, dear,” the Sunflower hurried on. “Besides, it’s shiny—”

“Shiny!”

“It—it soon will be, which is just the same, and the man is really estimable. He is nice and refined, and I am sure he—”

“Has seen better days.”

“Yes, and the weather is raw and beastly, and his clothes are threadbare. And you have many suits—”

“Five,” I corrected, “counting in the dark gray fishing outfit with the draggled pockets.”

“And he has none, no home, nothing—”

“Not even a Sunflower,”—putting my arm around her,—“wherefore he is deserving of all things. Give him the black suit, dear—nay, the best one, the very best one. Under high heaven for such lack there must be compensation!”

“You ARE a dear!” And the Sunflower moved to the door and looked back alluringly. “You are a PERFECT dear.”

And this after seven years, I marvelled, till she was back again, timid and apologetic.

“I—I gave him one of your white shirts. He wore a cheap horrid cotton thing, and I knew it would look ridiculous. And then his shoes were so slipshod, I let him have a pair of yours, the old ones with the narrow caps—”

“Old ones!”

“Well, they pinched horribly, and you know they did.”

It was ever thus the Sunflower vindicated things.

And so Leith Clay-Randolph came to Idlewild to stay, how

long I did not dream. Nor did I dream how often he was to come, for he was like an erratic comet. Fresh he would arrive, and cleanly clad, from grand folk who were his friends as I was his friend, and again, weary and worn, he would creep up the brier-rose path from the Montanas or Mexico. And without a word, when his WANDERLUST gripped him, he was off and away into that great mysterious underworld he called “The Road.”

“I could not bring myself to leave until I had thanked you, you of the open hand and heart,” he said, on the night he donned my good black suit.

And I confess I was startled when I glanced over the top of my paper and saw a lofty-browed and eminently respectable-looking gentleman, boldly and carelessly at ease. The Sunflower was right. He must have known better days for the black suit and white shirt to have effected such a transformation. Involuntarily I rose to my feet, prompted to meet him on equal ground. And then it was that the Clay-Randolph glamour descended upon me. He slept at Idlewild that night, and the next night, and for many nights. And he was a man to love. The Son of Anak, otherwise Rufus the Blue-Eyed, and also plebeianly known as Tots, rioted with him from brier-rose path to farthest orchard, scalped him in the haymow with barbaric yells, and once, with pharisaic zeal, was near to crucifying him under the attic roof beams. The Sunflower would have loved him for the Son of Anak’s sake, had she not loved him for his own. As for myself, let the Sunflower tell, in the times he elected to be gone, of how often I wondered when Leith would come back again, Leith the Lovable. Yet he was a man of whom we knew nothing. Beyond the fact that he was Kentucky-born, his past was a blank. He never spoke of it. And he was a man who prided himself upon his utter divorce of reason from emotion. To him the world spelled itself out in problems. I charged him once with being guilty of emotion when roaring round the den with the Son of Anak pickaback. Not so, he held. Could he not cuddle a sense-delight for the problem’s sake?

He was elusive. A man who intermingled nameless argot with polysyllabic and technical terms, he would seem sometimes the veriest criminal, in speech, face, expression, everything; at other times the cultured and polished gentleman, and again, the philosopher and scientist. But there was something glimmering; there which I never caught—flashes of sincerity, of real feeling, I imagined, which were sped ere I could grasp; echoes of the man he once was, possibly, or hints of the man behind the mask. But the mask he never lifted, and the real man we never knew.

“But the sixty days with which you were rewarded for your journalism?” I asked. “Never mind Loria. Tell me.”

“Well, if I must.” He flung one knee over the other with a short laugh.

“In a town that shall be nameless,” he began, “in fact, a city of fifty thousand, a fair and beautiful city wherein men slave for dollars and women for dress, an idea came to me. My front was prepossessing, as fronts go, and my pockets empty. I had in recollection a thought I once entertained of writing a reconciliation of Kant and Spencer. Not that they are reconcilable, of course, but the room offered for scientific satire—”

I waved my hand impatiently, and he broke off.

“I was just tracing my mental states for you, in order to show the genesis of the action,” he explained. “However, the idea came. What was the matter with a tramp sketch for the daily press? The Irreconcilability of the Constable and the Tramp, for instance? So I hit the DRAG (the drag, my dear fellow, is merely the street), or the high places, if you will, for a newspaper office. The elevator whisked me into the sky, and Cerberus, in the guise of an anaemic office boy, guarded the door. Consumption, one could see it at a glance; nerve, Irish, colossal; tenacity, undoubted; dead inside the year.

“‘Pale youth,’ quoth I, ‘I pray thee the way to the sanctum-sanctorum, to the Most High Cock-a-lorum.’

“He deigned to look at me, scornfully, with infinite weariness.

“‘G’wan an’ see the janitor. I don’t know nothin’ about the gas.’

“‘Nay, my lily-white, the editor.’

“‘Wich editor?’ he snapped like a young bullterrier. ‘Dramatic? Sportin’? Society? Sunday? Weekly? Daily? Telegraph? Local? News? Editorial? Wich?’

“Which, I did not know. ‘THE Editor,’ I proclaimed stoutly. ‘The ONLY Editor.’

“‘Aw, Spargo!’ he sniffed.

“‘Of course, Spargo,’ I answered. ‘Who else?’

“‘Gimme yer card,’ says he.

“‘My what?’

“‘Yer card—Say! Wot’s yer business, anyway?’

“And the anaemic Cerberus sized me up with so insolent an eye that I reached over and took him out of his chair. I knocked on his meagre chest with my fore knuckle, and fetched forth a weak, gaspy cough; but he looked at me unflinchingly, much like a defiant sparrow held in the hand.

“‘I am the census-taker Time,’ I boomed in sepulchral tones. ‘Beware lest I knock too loud.’

“‘Oh, I don’t know,’ he sneered.

“Whereupon I rapped him smartly, and he choked and turned purplish.

“‘Well, whatcher want?’ he wheezed with returning breath.

“‘I want Spargo, the only Spargo.’

“‘Then leave go, an’ I’ll glide an’ see.’

“‘No you don’t, my lily-white.’ And I took a tighter grip on his collar. ‘No bouncers in mine, understand! I’ll go along.’”

Leith dreamily surveyed the long ash of his cigar and turned to me. “Do you know, Anak, you can’t appreciate the joy of being the buffoon, playing the clown. You couldn’t do it if you wished. Your pitiful little conventions and smug assumptions of decency would prevent. But simply to turn loose your soul to every whimsicality, to play the fool unafraid of any possible result, why, that requires a man other than a householder and law-respecting citizen.

“However, as I was saying, I saw the only Spargo. He was a big, beefy, red-faced personage, full-jowled and double-chinned, sweating at his desk in his shirt-sleeves. It was August, you know. He was talking into a telephone when I entered, or swearing rather, I should say, and the while studying me with his eyes. When he hung up, he turned to me expectantly.

“‘You are a very busy man,’ I said.

“He jerked a nod with his head, and waited.

“‘And after all, is it worth it?’ I went on. ‘What does life mean that it should make you sweat? What justification do you find in sweat? Now look at me. I toil not, neither do I spin—’

“‘Who are you? What are you?’ he bellowed with a suddenness that was, well, rude, tearing the words out as a dog does a bone.

“‘A very pertinent question, sir,’ I acknowledged. ‘First, I am a man; next, a down-trodden American citizen. I am cursed with neither profession, trade, nor expectations. Like Esau, I am pottageless. My residence is everywhere; the sky is my coverlet. I am one of the dispossessed, a sansculotte, a proletarian, or, in simpler phraseology addressed to your understanding, a tramp.’

“‘What the hell—?’

“‘Nay, fair sir, a tramp, a man of devious ways and strange lodgements and multifarious—’

“‘Quit it!’ he shouted. ‘What do you want?’

“‘I want money.’

“He started and half reached for an open drawer where must have reposed a revolver, then bethought himself and growled, ‘This is no bank.’

“‘Nor have I checks to cash. But I have, sir, an idea, which, by your leave and kind assistance, I shall transmute into cash. In short, how does a tramp sketch, done by a tramp to the life, strike you? Are you open to it? Do your readers hunger for it? Do they crave after it? Can they be happy without it?’

“I thought for a moment that he would have apoplexy, but he quelled the unruly blood and said he liked my nerve. I thanked him and assured him I liked it myself. Then he offered me a cigar and said he thought he’d do business with me.

“‘But mind you,’ he said, when he had jabbed a bunch of copy paper into my hand and given me a pencil from his vest pocket, ‘mind you, I won’t stand for the high and fli

ghty philosophical, and I perceive you have a tendency that way. Throw in the local color, wads of it, and a bit of sentiment perhaps, but no slumgullion about political economy nor social strata or such stuff. Make it concrete, to the point, with snap and go and life, crisp and crackling and interesting—tumble?’

“And I tumbled and borrowed a dollar.

“‘Don’t forget the local color!’ he shouted after me through the door.

“And, Anak, it was the local color that did for me.

“The anaemic Cerberus grinned when I took the elevator. ‘Got the bounce, eh?’

“‘Nay, pale youth, so lily-white,’ I chortled, waving the copy paper; ‘not the bounce, but a detail. I’ll be City Editor in three months, and then I’ll make you jump.’

“And as the elevator stopped at the next floor down to take on a pair of maids, he strolled over to the shaft, and without frills or verbiage consigned me and my detail to perdition. But I liked him. He had pluck and was unafraid, and he knew, as well as I, that death clutched him close.”

“But how could you, Leith,” I cried, the picture of the consumptive lad strong before me, “how could you treat him so barbarously?”

Leith laughed dryly. “My dear fellow, how often must I explain to you your confusions? Orthodox sentiment and stereotyped emotion master you. And then your temperament! You are really incapable of rational judgments. Cerberus? Pshaw! A flash expiring, a mote of fading sparkle, a dim-pulsing and dying organism—pouf! a snap of the fingers, a puff of breath, what would you? A pawn in the game of life. Not even a problem. There is no problem in a stillborn babe, nor in a dead child. They never arrived. Nor did Cerberus. Now for a really pretty problem—”

The Son of the Wolf

The Son of the Wolf The Iron Heel

The Iron Heel Before Adam

Before Adam Smoke Bellew

Smoke Bellew The Call of the Wild

The Call of the Wild The Valley of the Moon Jack London

The Valley of the Moon Jack London Burning Daylight

Burning Daylight The Sea Wolf

The Sea Wolf White Fang

White Fang A Daughter of the Snows

A Daughter of the Snows The Night-Born

The Night-Born A Son Of The Sun

A Son Of The Sun Dutch Courage and Other Stories

Dutch Courage and Other Stories The People of the Abyss

The People of the Abyss Michael, Brother of Jerry

Michael, Brother of Jerry Love of Life, and Other Stories

Love of Life, and Other Stories Lost Face

Lost Face The Road

The Road Love of Life

Love of Life The Turtles of Tasman

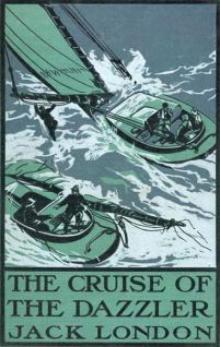

The Turtles of Tasman The Cruise of The Dazzler

The Cruise of The Dazzler The Heathen

The Heathen The Scab

The Scab The Faith of Men

The Faith of Men Adventure

Adventure The Assassination Bureau, Ltd.

The Assassination Bureau, Ltd. The Call of the Wild, White Fang, and Other Stories

The Call of the Wild, White Fang, and Other Stories The Call of the Wild and Selected Stories

The Call of the Wild and Selected Stories Jerry of the Islands

Jerry of the Islands Hearts of Three

Hearts of Three The House of Pride

The House of Pride Moon-Face and Other Stories

Moon-Face and Other Stories Children of the Frost

Children of the Frost South Sea Tales

South Sea Tales The Strength of the Strong

The Strength of the Strong The Jacket (The Star-Rover)

The Jacket (The Star-Rover) The Little Lady of the Big House

The Little Lady of the Big House John Barleycorn

John Barleycorn ADaugter of Snows

ADaugter of Snows The Mutiny of the Elsinore

The Mutiny of the Elsinore Northland Stories

Northland Stories Tales of the Fish Patrol

Tales of the Fish Patrol Call of the Wild and White Fang (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Call of the Wild and White Fang (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Valley of the Moon

The Valley of the Moon The Cruise of the Snark

The Cruise of the Snark The Game

The Game An Autobiography of Jack London

An Autobiography of Jack London