- Home

- Jack London

The Sea Wolf Page 18

The Sea Wolf Read online

Page 18

I broke short off in the middle of a sentence. The present, with all its perils and anxieties, rushed upon me with stunning force. It smote Miss Brewster likewise, a vague and nameless terror rushing into her eyes as she regarded Wolf Larsen.

He rose to his feet and laughed awkwardly. The sound of it was metallic.

“Oh, don’t mind me,” he said, with a self-depreciatory wave of his hand. “I don’t count. Go on, go on, I pray you.”

But the gates of speech were closed, and we, too, rose from the table and laughed awkwardly.

Chapter XXI

* * *

The chagrin Wolf Larsen felt from being ignored by Maud Brewster and me in the conversation at table had to express itself in some fashion, and it fell to Thomas Mugridge to be the victim. He had not mended his ways nor his shirt, though the latter he contended he had changed. The garment itself did not bear out the assertion, nor did the accumulations of grease on stove and pot and pan attest a general cleanliness.

“I’ve given you warning, Cooky,” Wolf Larsen said, “and now you’ve got to take your medicine.”

Mugridge’s face turned white under its sooty veneer, and when Wolf Larsen called for a rope and a couple of men, the miserable Cockney fled wildly out of the galley and dodged and ducked about the deck with the grinning crew in pursuit. Few things could have been more to their liking than to give him a tow over the side, for to the forecastle he had sent messes and concoctions of the vilest order. Conditions favoured the undertaking. The Ghost was slipping through the water at no more than three miles an hour, and the sea was fairly calm. But Mugridge had little stomach for a dip in it. Possibly he had seen men towed before. Besides, the water was frightfully cold, and his was anything but a rugged constitution.

As usual, the watches below and the hunters turned out for what promised sport. Mugridge seemed to be in rabid fear of the water, and he exhibited a nimbleness and speed we did not dream he possessed. Cornered in the right-angle of the poop and galley, he sprang like a cat to the top of the cabin and ran aft. But his pursuers forestalling him, he doubled back across the cabin, passed over the galley, and gained the deck by means of the steeragescuttle. Straight forward he raced, the boat-puller Harrison at his heels and gaining on him. But Mugridge, leaping suddenly, caught the jib-boom-lift. It happened in an instant. Holding his weight by his arms, and in mid-air doubling his body at the hips, he let fly with both feet. The oncoming Harrison caught the kick squarely in the pit of the stomach, groaned involuntarily, and doubled up and sank backward to the deck.

Hand-clapping and roars of laughter from the hunters greeted the exploit, while Mugridge, eluding half of his pursuers at the foremast, ran aft and through the remainder like a runner on the football field. Straight aft he held, to the poop and along the poop to the stern. So great was his speed that as he curved past the corner of the cabin he slipped and fell. Nilson was standing at the wheel, and the Cockney’s hurtling body struck his legs. Both went down together, but Mugridge alone arose. By some freak of pressures, his frail body had snapped the strong man’s leg like a pipe-stem.

Parsons took the wheel, and the pursuit continued. Round and round the decks they went, Mugridge sick with fear, the sailors hallooing and shouting directions to one another, and the hunters bellowing encouragement and laughter. Mugridge went down on the fore-hatch under three men; but he emerged from the mass like an eel, bleeding at the mouth, the offending shirt ripped into tatters, and sprang for the main-rigging. Up he went, clear up, beyond the ratlines, to the very masthead.

Half-a-dozen sailors swarmed to the crosstrees after him, where they clustered and waited while two of their number, Oofty-Oofty and Black (who was Latimer’s boat-steerer), continued up the thin steel stays, lifting their bodies higher and higher by means of their arms.

It was a perilous undertaking, for, at a height of over a hundred feet from the deck, holding on by their hands, they were not in the best of positions to protect themselves from Mugridge’s feet. And Mugridge kicked savagely, till the Kanaka, hanging on with one hand, seized the Cockney’s foot with the other. Black duplicated the performance a moment later with the other foot. Then the three writhed together in a swaying tangle, struggling, sliding, and falling into the arms of their mates on the crosstrees.

The aerial battle was over, and Thomas Mugridge, whining and gibbering, his mouth flecked with bloody foam, was brought down to deck. Wolf Larsen rove a bowline in a piece of rope and slipped it under his shoulders. Then he was carried aft and flung into the sea. Forty, — fifty, — sixty feet of line ran out, when Wolf Larsen cried “Belay!” Oofty-Oofty took a turn on a bitt, the rope tautened, and the Ghost, lunging onward, jerked the cook to the surface.

It was a pitiful spectacle. Though he could not drown, and was nine-lived in addition, he was suffering all the agonies of halfdrowning. The Ghost was going very slowly, and when her stern lifted on a wave and she slipped forward she pulled the wretch to the surface and gave him a moment in which to breathe; but between each lift the stern fell, and while the bow lazily climbed the next wave the line slacked and he sank beneath.

I had forgotten the existence of Maud Brewster, and I remembered her with a start as she stepped lightly beside me. It was her first time on deck since she had come aboard. A dead silence greeted her appearance.

“What is the cause of the merriment?” she asked.

“Ask Captain Larsen,” I answered composedly and coldly, though inwardly my blood was boiling at the thought that she should be witness to such brutality.

She took my advice and was turning to put it into execution, when her eyes lighted on Oofty-Oofty, immediately before her, his body instinct with alertness and grace as he held the turn of the rope.

“Are you fishing?” she asked him.

He made no reply. His eyes, fixed intently on the sea astern, suddenly flashed.

“Shark ho, sir!” he cried.

“Heave in! Lively! All hands tail on!” Wolf Larsen shouted, springing himself to the rope in advance of the quickest.

Mugridge had heard the Kanaka’s warning cry and was screaming madly. I could see a black fin cutting the water and making for him with greater swiftness than he was being pulled aboard. It was an even toss whether the shark or we would get him, and it was a matter of moments. When Mugridge was directly beneath us, the stern descended the slope of a passing wave, thus giving the advantage to the shark. The fin disappeared. The belly flashed white in swift upward rush. Almost equally swift, but not quite, was Wolf Larsen. He threw his strength into one tremendous jerk. The Cockney’s body left the water; so did part of the shark’s. He drew up his legs, and the man-eater seemed no more than barely to touch one foot, sinking back into the water with a splash. But at the moment of contact Thomas Mugridge cried out. Then he came in like a fresh-caught fish on a line, clearing the rail generously and striking the deck in a heap, on hands and knees, and rolling over.

But a fountain of blood was gushing forth. The right foot was missing, amputated neatly at the ankle. I looked instantly to Maud Brewster. Her face was white, her eyes dilated with horror. She was gazing, not at Thomas Mugridge, but at Wolf Larsen. And he was aware of it, for he said, with one of his short laughs:

“Man-play, Miss Brewster. Somewhat rougher, I warrant, than what you have been used to, but still-man-play. The shark was not in the reckoning. It —“

But at this juncture, Mugridge, who had lifted his head and ascertained the extent of his loss, floundered over on the deck and buried his teeth in Wolf Larsen’s leg. Wolf Larsen stooped, coolly, to the Cockney, and pressed with thumb and finger at the rear of the jaws and below the ears. The jaws opened with reluctance, and Wolf Larsen stepped free.

“As I was saying,” he went on, as though nothing unwonted had happened, “the shark was not in the reckoning. It was — ahem shall we say Providence?”

She gave no sign that she had heard, though the expression of her eyes changed to one of inexpressible loathing as

she started to turn away. She no more than started, for she swayed and tottered, and reached her hand weakly out to mine. I caught her in time to save her from falling, and helped her to a seat on the cabin. I thought she might faint outright, but she controlled herself.

“Will you get a tourniquet, Mr. Van Weyden,” Wolf Larsen called to me.

I hesitated. Her lips moved, and though they formed no words, she commanded me with her eyes, plainly as speech, to go to the help of the unfortunate man. “Please,” she managed to whisper, and I could but obey.

By now I had developed such skill at surgery that Wolf Larsen, with a few words of advice, left me to my task with a couple of sailors for assistants. For his task he elected a vengeance on the shark. A heavy swivel-hook, baited with fat salt-pork, was dropped overside; and by the time I had compressed the severed veins and arteries, the sailors were singing and heaving in the offending monster. I did not see it myself, but my assistants, first one and then the other, deserted me for a few moments to run amidships and look at what was going on. The shark, a sixteen-footer, was hoisted up against the main-rigging. Its jaws were pried apart to their greatest extension, and a stout stake, sharpened at both ends, was so inserted that when the pries were removed the spread jaws were fixed upon it. This accomplished, the hook was cut out. The shark dropped back into the sea, helpless, yet with its full strength, doomed — to lingering starvation — a living death less meet for it than for the man who devised the punishment.

Chapter XXII

* * *

I knew what it was as she came toward me. For ten minutes I had watched her talking earnestly with the engineer, and now, with a sign for silence, I drew her out of earshot of the helmsman. Her face was white and set; her large eyes, larger than usual what of the purpose in them, looked penetratingly into mine. I felt rather timid and apprehensive, for she had come to search Humphrey Van Weyden’s soul, and Humphrey Van Weyden had nothing of which to be particularly proud since his advent on the Ghost.

We walked to the break of the poop, where she turned and faced me. I glanced around to see that no one was within hearing distance.

“What is it?” I asked gently; but the expression of determination on her face did not relax.

“I can readily understand,” she began, “that this morning’s affair was largely an accident; but I have been talking with Mr. Haskins. He tells me that the day we were rescued, even while I was in the cabin, two men were drowned, deliberately drowned — murdered.”

There was a query in her voice, and she faced me accusingly, as though I were guilty of the deed, or at least a party to it.

“The information is quite correct,” I answered. “The two men were murdered.”

“And you permitted it!” she cried.

“I was unable to prevent it, is a better way of phrasing it,” I replied, still gently.

“But you tried to prevent it?” There was an emphasis on the “tried,” and a pleading little note in her voice.

“Oh, but you didn’t,” she hurried on, divining my answer. “But why didn’t you?”

I shrugged my shoulders. “You must remember, Miss Brewster, that you are a new inhabitant of this little world, and that you do not yet understand the laws which operate within it. You bring with you certain fine conceptions of humanity, manhood, conduct, and such things; but here you will find them misconceptions. I have found it so,” I added, with an involuntary sigh.

She shook her head incredulously.

“What would you advise, then?” I asked. “That I should take a knife, or a gun, or an axe, and kill this man?”

She half started back.

“No, not that!”

“Then what should I do? Kill myself?”

“You speak in purely materialistic terms,” she objected. “There is such a thing as moral courage, and moral courage is never without effect.”

“Ah,” I smiled, “you advise me to kill neither him nor myself, but to let him kill me.” I held up my hand as she was about to speak. “For moral courage is a worthless asset on this little floating world. Leach, one of the men who were murdered, had moral courage to an unusual degree. So had the other man, Johnson. Not only did it not stand them in good stead, but it destroyed them. And so with me if I should exercise what little moral courage I may possess.

“You must understand, Miss Brewster, and understand clearly, that this man is a monster. He is without conscience. Nothing is sacred to him, nothing is too terrible for him to do. It was due to his whim that I was detained aboard in the first place. It is due to his whim that I am still alive. I do nothing, can do nothing, because I am a slave to this monster, as you are now a slave to him; because I desire to live, as you will desire to live; because I cannot fight and overcome him, just as you will not be able to fight and overcome him.”

She waited for me to go on.

“What remains? Mine is the role of the weak. I remain silent and suffer ignominy, as you will remain silent and suffer ignominy. And it is well. It is the best we can do if we wish to live. The battle is not always to the strong. We have not the strength with which to fight this man; we must dissimulate, and win, if win we can, by craft. If you will be advised by me, this is what you will do. I know my position is perilous, and I may say frankly that yours is even more perilous. We must stand together, without appearing to do so, in secret alliance. I shall not be able to side with you openly, and, no matter what indignities may be put upon me, you are to remain likewise silent. We must provoke no scenes with this man, nor cross his will. And we must keep smiling faces and be friendly with him no matter how repulsive it may be.”

She brushed her hand across her forehead in a puzzled way, saying, “Still I do not understand.”

“You must do as I say,” I interrupted authoritatively, for I saw Wolf Larsen’s gaze wandering toward us from where he paced up and down with Latimer amidships. “Do as I say, and ere long you will find I am right.”

“What shall I do, then?” she asked, detecting the anxious glance I had shot at the object of our conversation, and impressed, I flatter myself, with the earnestness of my manner.

“Dispense with all the moral courage you can,” I said briskly. “Don’t arouse this man’s animosity. Be quite friendly with him, talk with him, discuss literature and art with him — he is fond of such things. You will find him an interested listener and no fool. And for your own sake try to avoid witnessing, as much as you can, the brutalities of the ship. It will make it easier for you to act your part.”

“I am to lie,” she said in steady, rebellious tones, “by speech and action to lie.”

Wolf Larsen had separated from Latimer and was coming toward us. I was desperate.

“Please, please understand me,” I said hurriedly, lowering my voice. “All your experience of men and things is worthless here. You must begin over again. I know, — I can see it — you have, among other ways, been used to managing people with your eyes, letting your moral courage speak out through them, as it were. You have already managed me with your eyes, commanded me with them. But don’t try it on Wolf Larsen. You could as easily control a lion, while he would make a mock of you. He would — I have always been proud of the fact that I discovered him,” I said, turning the conversation as Wolf Larsen stepped on the poop and joined us. “The editors were afraid of him and the publishers would have none of him. But I knew, and his genius and my judgment were vindicated when he made that magnificent hit with his ‘Forge.’”

“And it was a newspaper poem,” she said glibly.

“It did happen to see the light in a newspaper,” I replied, “but not because the magazine editors had been denied a glimpse at it.”

“We were talking of Harris,” I said to Wolf Larsen.

“Oh, yes,” he acknowledged. “I remember the ‘Forge.’ Filled with pretty sentiments and an almighty faith in human illusions. By the way, Mr. Van Weyden, you’d better look in on Cooky. He’s complaining and restless.”

Thus

was I bluntly dismissed from the poop, only to find Mugridge sleeping soundly from the morphine I had given him. I made no haste to return on deck, and when I did I was gratified to see Miss Brewster in animated conversation with Wolf Larsen. As I say, the sight gratified me. She was following my advice. And yet I was conscious of a slight shock or hurt in that she was able to do the thing I had begged her to do and which she had notably disliked.

Chapter XXIII

* * *

Brave winds, blowing fair, swiftly drove the Ghost northward into the seal herd. We encountered it well up to the forty-fourth parallel, in a raw and stormy sea across which the wind harried the fog-banks in eternal flight. For days at a time we could never see the sun nor take an observation; then the wind would sweep the face of the ocean clean, the waves would ripple and flash, and we would learn where we were. A day of clear weather might follow, or three days or four, and then the fog would settle down upon us, seemingly thicker than ever.

The hunting was perilous; yet the boats, lowered day after day, were swallowed up in the grey obscurity, and were seen no more till nightfall, and often not till long after, when they would creep in like sea-wraiths, one by one, out of the grey. Wainwright — the hunter whom Wolf Larsen had stolen with boat and men — took advantage of the veiled sea and escaped. He disappeared one morning in the encircling fog with his two men, and we never saw them again, though it was not many days when we learned that they had passed from schooner to schooner until they finally regained their own.

This was the thing I had set my mind upon doing, but the opportunity never offered. It was not in the mate’s province to go out in the boats, and though I manoeuvred cunningly for it, Wolf Larsen never granted me the privilege. Had he done so, I should have managed somehow to carry Miss Brewster away with me. As it was, the situation was approaching a stage which I was afraid to consider. I involuntarily shunned the thought of it, and yet the thought continually arose in my mind like a haunting spectre.

The Son of the Wolf

The Son of the Wolf The Iron Heel

The Iron Heel Before Adam

Before Adam Smoke Bellew

Smoke Bellew The Call of the Wild

The Call of the Wild The Valley of the Moon Jack London

The Valley of the Moon Jack London Burning Daylight

Burning Daylight The Sea Wolf

The Sea Wolf White Fang

White Fang A Daughter of the Snows

A Daughter of the Snows The Night-Born

The Night-Born A Son Of The Sun

A Son Of The Sun Dutch Courage and Other Stories

Dutch Courage and Other Stories The People of the Abyss

The People of the Abyss Michael, Brother of Jerry

Michael, Brother of Jerry Love of Life, and Other Stories

Love of Life, and Other Stories Lost Face

Lost Face The Road

The Road Love of Life

Love of Life The Turtles of Tasman

The Turtles of Tasman The Cruise of The Dazzler

The Cruise of The Dazzler The Heathen

The Heathen The Scab

The Scab The Faith of Men

The Faith of Men Adventure

Adventure The Assassination Bureau, Ltd.

The Assassination Bureau, Ltd. The Call of the Wild, White Fang, and Other Stories

The Call of the Wild, White Fang, and Other Stories The Call of the Wild and Selected Stories

The Call of the Wild and Selected Stories Jerry of the Islands

Jerry of the Islands Hearts of Three

Hearts of Three The House of Pride

The House of Pride Moon-Face and Other Stories

Moon-Face and Other Stories Children of the Frost

Children of the Frost South Sea Tales

South Sea Tales The Strength of the Strong

The Strength of the Strong The Jacket (The Star-Rover)

The Jacket (The Star-Rover) The Little Lady of the Big House

The Little Lady of the Big House John Barleycorn

John Barleycorn ADaugter of Snows

ADaugter of Snows The Mutiny of the Elsinore

The Mutiny of the Elsinore Northland Stories

Northland Stories Tales of the Fish Patrol

Tales of the Fish Patrol Call of the Wild and White Fang (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Call of the Wild and White Fang (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Valley of the Moon

The Valley of the Moon The Cruise of the Snark

The Cruise of the Snark The Game

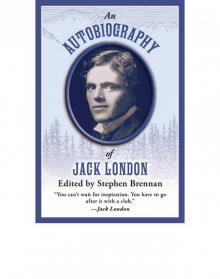

The Game An Autobiography of Jack London

An Autobiography of Jack London