- Home

- Jack London

ADaugter of Snows Page 18

ADaugter of Snows Read online

Page 18

"Don't be a fool! I like you too well to see you make yourself one. The play's been too quick, that is all. Your eye lost it. Listen. We've kept it quiet, but she's in with the elect on French Hill. Her claim's prospected the richest of the outfit. Present indication half a million at least. In her own name, no strings attached. Couldn't she take that and go anywhere in the world and reinstate herself? And for that matter, you might presume that I am marrying her for spoils. Frona, she cares for me, and in your ear, she's too good for me. My hope is that the future will make up. But never mind that—haven't got the time now.

"You consider her affection sudden, eh? Let me tell you we've been growing into each other from the time I came into the country, and with our eyes open. St. Vincent ? Pshaw! I knew it all the time. She got it into her head that the whole of him wasn't worth a little finger of you, and she tried to break things up. You'll never know how she worked with him. I told her she didn't know the Welse, and she said so, too, after. So there it is; take it or leave it."

"But what do you think about St. Vincent ?"

"What I think is neither here nor there; but I'll tell you honestly that I back her judgment. But that's not the point. What are you going to do about it? about her? now?"

She did not answer, but went back to the waiting group. Lucile saw her coming and watched her face.

"He's been telling you—?"

"That I am a fool," Frona answered. "And I think I am." And with a smile, "I take it on faith that I am, anyway. I—I can't reason it out just now, but. . ."

Captain Alexander discovered a prenuptial joke just about then, and led the way over to the stove to crack it upon the colonel, and Vance went along to see fair play.

"It's the first time," Lucile was saying, "and it means more to me, so much more, than to . . . most women. I am afraid. It is a terrible thing for me to do. But I do love him, I do!" And when the joke had been duly digested and they came back, she was sobbing, "Dear, dear Frona."

It was just the moment, better than he could have chosen; and capped and mittened, without knocking, Jacob Welse came in.

"The uninvited guest," was his greeting. "Is it all over? So?" And he swallowed Lucile up in his huge bearskin. "Colonel, your hand, and your pardon for my intruding, and your regrets for not giving me the word. Come, out with them! Hello, Corliss! Captain Alexander, a good day."

"What have I done?" Frona wailed, received the bear-hug, and managed to press his hand till it almost hurt.

"Had to back the game," he whispered; and this time his hand did hurt.

"Now, colonel, I don't know what your plans are, and I don't care. Call them off. I've got a little spread down to the house, and the only honest case of champagne this side of Circle. Of course, you're coming, Corliss, and—" His eye roved past Captain Alexander with hardly a pause.

"Of course," came the answer like a flash, though the Chief Magistrate of the Northwest had had time to canvass the possible results of such unofficial action. "Got a hack?"

Jacob Welse laughed and held up a moccasined foot. "Walking be—chucked!" The captain started impulsively towards the door. "I'll have the sleds up before you're ready. Three of them, and bells galore!"

So Trethaway's forecast was correct, and Dawson vindicated its agglutinativeness by rubbing its eyes when three sleds, with three scarlet-tuniced policemen swinging the whips, tore down its main street; and it rubbed its eyes again when it saw the occupants thereof.

"We shall live quietly," Lucile told Frona. "The Klondike is not all the world, and the best is yet to come."

But Jacob Welse said otherwise. "We've got to make this thing go," he said to Captain Alexander, and Captain Alexander said that he was unaccustomed to backing out.

Mrs. Schoville emitted preliminary thunders, marshalled the other women, and became chronically seismic and unsafe.

Lucile went nowhere save to Frona's. But Jacob Welse, who rarely went anywhere, was often to be found by Colonel Trethaway's fireside, and not only was he to be found there, but he usually brought somebody along. "Anything on hand this evening?" he was wont to say on casual meeting. "No? Then come along with me." Sometimes he said it with lamb-like innocence, sometimes with a challenge brooding under his bushy brows, and rarely did he fail to get his man. These men had wives, and thus were the germs of dissolution sown in the ranks of the opposition.

Then, again, at Colonel Trethaway's there was something to be found besides weak tea and small talk; and the correspondents, engineers, and gentlemen rovers kept the trail well packed in that direction, though it was the Kings, to a man, who first broke the way. So the Trethaway cabin became the centre of things, and, backed commercially, financially, and officially, it could not fail to succeed socially.

The only bad effect of all this was to make the lives of Mrs. Schoville and divers others of her sex more monotonous, and to cause them to lose faith in certain hoary and inconsequent maxims. Furthermore, Captain Alexander, as highest official, was a power in the land, and Jacob Welse was the Company, and there was a superstition extant concerning the unwisdom of being on indifferent terms with the Company. And the time was not long till probably a bare half-dozen remained in outer cold, and they were considered a warped lot, anyway.

CHAPTER XXII

Quite an exodus took place in Dawson in the spring. Men, because they had made stakes, and other men, because they had made none, bought up the available dogs and rushed out for Dyea over the last ice. Incidentally, it was discovered that Dave Harney possessed most of these dogs.

"Going out?" Jacob Welse asked him on a day when the meridian sun for the first time felt faintly warm to the naked skin.

"Well, I calkilate not. I'm clearin' three dollars a pair on the moccasins I cornered, to say nothing but saw wood on the boots. Say, Welse, not that my nose is out of joint, but you jest cinched me everlastin' on sugar, didn't you?"

Jacob Welse smiled.

"And by the Jimcracky I'm squared! Got any rubber boots?"

"No; went out of stock early in the winter." Dave snickered slowly.

"And I'm the pertickler party that hocus-pocused 'em."

"Not you. I gave special orders to the clerks. They weren't sold in lots."

"No more they wa'n't. One man to the pair and one pair to the man, and a couple of hundred of them; but it was my dust they chucked into the scales an nobody else's. Drink? Don't mind. Easy! Put up your sack. Call it rebate, for I kin afford it. . . Goin' out? Not this year, I guess. Wash-up's comin'."

A strike on Henderson the middle of April, which promised to be sensational, drew St. Vincent to Stewart River . And a little later, Jacob Welse, interested on Gallagher Gulch and with an eye riveted on the copper mines of White River , went up into the same district, and with him went Frona, for it was more vacation than business. In the mean time, Corliss and Bishop, who had been on trail for a month or more running over the Mayo and McQuestion Country, rounded up on the left fork of Henderson , where a block of claims waited to be surveyed.

But by May, spring was so far advanced that travel on the creeks became perilous, and on the last of the thawing ice the miners travelled down to the bunch of islands below the mouth of the Stewart, where they went into temporary quarters or crowded the hospitality of those who possessed cabins. Corliss and Bishop located on Split-up Island (so called through the habit parties from the Outside had of dividing there and going several ways), where Tommy McPherson was comfortably situated. A couple of days later, Jacob Welse and Frona arrived from a hazardous trip out of White River , and pitched tent on the high ground at the upper end of Split-up. A few chechaquos , the first of the spring rush, strung in exhausted and went into camp against the breaking of the river. Also, there were still men going out who, barred by the rotten ice, came ashore to build poling-boats and await the break-up or to negotiate with the residents for canoes. Notably among these was the Baron Courbertin.

"Ah! Excruciating! Magnificent! Is it not?"

So Frona first

ran across him on the following day. "What?" she asked, giving him her hand.

"You! You!" doffing his cap. "It is a delight!"

"I am sure—" she began.

"No! No!" He shook his curly mop warmly. "It is not you. See!" He turned to a Peterborough , for which McPherson had just mulcted him of thrice its value. "The canoe! Is it not—not—what you Yankees call—a bute?"

"Oh, the canoe," she repeated, with a falling inflection of chagrin.

"No! No! Pardon!" He stamped angrily upon the ground. "It is not so. It is not you. It is not the canoe. It is—ah! I have it now! It is your promise. One day, do you not remember, at Madame Schoville's, we talked of the canoe, and of my ignorance, which was sad, and you promised, you said—"

"I would give you your first lesson?"

"And is it not delightful? Listen! Do you not hear? The rippling—ah! the rippling!—deep down at the heart of things! Soon will the water run free. Here is the canoe! Here we meet! The first lesson! Delightful! Delightful!"

The next island below Split-up was known as Roubeau's Island , and was separated from the former by a narrow back-channel. Here, when the bottom had about dropped out of the trail, and with the dogs swimming as often as not, arrived St. Vincent —the last man to travel the winter trail. He went into the cabin of John Borg, a taciturn, gloomy individual, prone to segregate himself from his kind. It was the mischance of St. Vincent 's life that of all cabins he chose Borg's for an abiding-place against the break-up.

"All right," the man said, when questioned by him. "Throw your blankets into the corner. Bella'll clear the litter out of the spare bunk."

Not till evening did he speak again, and then, "You're big enough to do your own cooking. When the woman's done with the stove you can fire away."

The woman, or Bella, was a comely Indian girl, young, and the prettiest St. Vincent had run across. Instead of the customary greased swarthiness of the race, her skin was clear and of a light-bronze tone, and her features less harsh, more felicitously curved, than those common to the blood.

After supper, Borg, both elbows on table and huge misshapen hands supporting chin and jaws, sat puffing stinking Siwash tobacco and staring straight before him. It would have seemed ruminative, the stare, had his eyes been softer or had he blinked; as it was, his face was set and trance-like.

"Have you been in the country long?" St. Vincent asked, endeavoring to make conversation.

Borg turned his sullen-black eyes upon him, and seemed to look into him and through him and beyond him, and, still regarding him, to have forgotten all about him. It was as though he pondered some great and weighty matter—probably his sins, the correspondent mused nervously, rolling himself a cigarette. When the yellow cube had dissipated itself in curling fragrance, and he was deliberating about rolling a second, Borg suddenly spoke.

"Fifteen years," he said, and returned to his tremendous cogitation.

Thereat, and for half an hour thereafter, St. Vincent , fascinated, studied his inscrutable countenance. To begin with, it was a massive head, abnormal and top-heavy, and its only excuse for being was the huge bull-throat which supported it. It had been cast in a mould of elemental generousness, and everything about it partook of the asymmetrical crudeness of the elemental. The hair, rank of growth, thick and unkempt, matted itself here and there into curious splotches of gray; and again, grinning at age, twisted itself into curling locks of lustreless black—locks of unusual thickness, like crooked fingers, heavy and solid. The shaggy whiskers, almost bare in places, and in others massing into bunchgrass-like clumps, were plentifully splashed with gray. They rioted monstrously over his face and fell raggedly to his chest, but failed to hide the great hollowed cheeks or the twisted mouth. The latter was thin-lipped and cruel, but cruel only in a passionless sort of way. But the forehead was the anomaly,—the anomaly required to complete the irregularity of the face. For it was a perfect forehead, full and broad, and rising superbly strong to its high dome. It was as the seat and bulwark of some vast intelligence; omniscience might have brooded there.

Bella, washing the dishes and placing them away on the shelf behind Borg's back, dropped a heavy tin cup. The cabin was very still, and the sharp rattle came without warning. On the instant, with a brute roar, the chair was overturned and Borg was on his feet, eyes blazing and face convulsed. Bella gave an inarticulate, animal-like cry of fear and cowered at his feet. St. Vincent felt his hair bristling, and an uncanny chill, like a jet of cold air, played up and down his spine. Then Borg righted the chair and sank back into his old position, chin on hands and brooding ponderously. Not a word was spoken, and Bella went on unconcernedly with the dishes, while St. Vincent rolled, a shaky cigarette and wondered if it had been a dream.

Jacob Welse laughed when the correspondent told him. "Just his way," he said; "for his ways are like his looks,—unusual. He's an unsociable beast. Been in the country more years than he can number acquaintances. Truth to say, I don't think he has a friend in all Alaska , not even among the Indians, and he's chummed thick with them off and on. 'Johnny Sorehead,' they call him, but it might as well be 'Johnny Break-um-head,' for he's got a quick temper and a rough hand. Temper! Some little misunderstanding popped up between him and the agent at Arctic City . He was in the right, too,—agent's mistake,—but he tabooed the Company on the spot and lived on straight meat for a year. Then I happened to run across him at Tanana Station, and after due explanations he consented to buy from us again."

"Got the girl from up the head-waters of the White," Bill Brown told St. Vincent . "Welse thinks he's pioneering in that direction, but Borg could give him cards and spades on it and then win out. He's been over the ground years ago. Yes, strange sort of a chap. Wouldn't hanker to be bunk-mates with him."

But St. Vincent did not mind the eccentricities of the man, for he spent most of his time on Split-up Island with Frona and the Baron. One day, however, and innocently, he ran foul of him. Two Swedes, hunting tree-squirrels from the other end of Roubeau Island , had stopped to ask for matches and to yarn a while in the warm sunshine of the clearing. St. Vincent and Borg were accommodating them, the latter for the most part in meditative monosyllables. Just to the rear, by the cabin-door, Bella was washing clothes. The tub was a cumbersome home-made affair, and half-full of water, was more than a fair match for an ordinary woman. The correspondent noticed her struggling with it, and stepped back quickly to her aid.

With the tub between them, they proceeded to carry it to one side in order to dump it where the ground drained from the cabin. St. Vincent slipped in the thawing snow and the soapy water splashed up. Then Bella slipped, and then they both slipped. Bella giggled and laughed, and St. Vincent laughed back. The spring was in the air and in their blood, and it was very good to be alive. Only a wintry heart could deny a smile on such a day. Bella slipped again, tried to recover, slipped with the other foot, and sat down abruptly. Laughing gleefully, both of them, the correspondent caught her hands to pull her to her feet. With a bound and a bellow, Borg was upon them. Their hands were torn apart and St. Vincent thrust heavily backward. He staggered for a couple of yards and almost fell. Then the scene of the cabin was repeated. Bella cowered and grovelled in the muck, and her lord towered wrathfully over her.

"Look you," he said in stifled gutturals, turning to St. Vincent . "You sleep in my cabin and you cook. That is enough. Let my woman alone."

Things went on after that as though nothing had happened; St. Vincent gave Bella a wide berth and seemed to have forgotten her existence. But the Swedes went back to their end of the island, laughing at the trivial happening which was destined to be significant.

CHAPTER XXIII

Spring, smiting with soft, warm hands, had come like a miracle, and now lingered for a dreamy spell before bursting into full-blown summer. The snow had left the bottoms and valleys and nestled only on the north slopes of the ice-scarred ridges. The glacial drip was already in evidence, and every creek in roaring spate. Each day the sun rose ea

rlier and stayed later. It was now chill day by three o'clock and mellow twilight at nine. Soon a golden circle would be drawn around the sky, and deep midnight become bright as high noon. The willows and aspens had long since budded, and were now decking themselves in liveries of fresh young green, and the sap was rising in the pines.

Mother nature had heaved her waking sigh and gone about her brief business. Crickets sang of nights in the stilly cabins, and in the sunshine mosquitoes crept from out hollow logs and snug crevices among the rocks,—big, noisy, harmless fellows, that had procreated the year gone, lain frozen through the winter, and were now rejuvenated to buzz through swift senility to second death. All sorts of creeping, crawling, fluttering life came forth from the warming earth and hastened to mature, reproduce, and cease. Just a breath of balmy air, and then the long cold frost again—ah! they knew it well and lost no time. Sand martins were driving their ancient tunnels into the soft clay banks, and robins singing on the spruce-garbed islands. Overhead the woodpecker knocked insistently, and in the forest depths the partridge boom-boomed and strutted in virile glory.

But in all this nervous haste the Yukon took no part. For many a thousand miles it lay cold, unsmiling, dead. Wild fowl, driving up from the south in wind-jamming wedges, halted, looked vainly for open water, and quested dauntlessly on into the north. From bank to bank stretched the savage ice. Here and there the water burst through and flooded over, but in the chill nights froze solidly as ever. Tradition has it that of old time the Yukon lay unbroken through three long summers, and on the face of it there be traditions less easy of belief.

So summer waited for open water, and the tardy Yukon took to stretching of days and cracking its stiff joints. Now an air-hole ate into the ice, and ate and ate; or a fissure formed, and grew, and failed to freeze again. Then the ice ripped from the shore and uprose bodily a yard. But still the river was loth to loose its grip. It was a slow travail, and man, used to nursing nature with pigmy skill, able to burst waterspouts and harness waterfalls, could avail nothing against the billions of frigid tons which refused to run down the hill to Bering Sea.

The Son of the Wolf

The Son of the Wolf The Iron Heel

The Iron Heel Before Adam

Before Adam Smoke Bellew

Smoke Bellew The Call of the Wild

The Call of the Wild The Valley of the Moon Jack London

The Valley of the Moon Jack London Burning Daylight

Burning Daylight The Sea Wolf

The Sea Wolf White Fang

White Fang A Daughter of the Snows

A Daughter of the Snows The Night-Born

The Night-Born A Son Of The Sun

A Son Of The Sun Dutch Courage and Other Stories

Dutch Courage and Other Stories The People of the Abyss

The People of the Abyss Michael, Brother of Jerry

Michael, Brother of Jerry Love of Life, and Other Stories

Love of Life, and Other Stories Lost Face

Lost Face The Road

The Road Love of Life

Love of Life The Turtles of Tasman

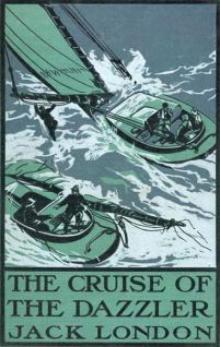

The Turtles of Tasman The Cruise of The Dazzler

The Cruise of The Dazzler The Heathen

The Heathen The Scab

The Scab The Faith of Men

The Faith of Men Adventure

Adventure The Assassination Bureau, Ltd.

The Assassination Bureau, Ltd. The Call of the Wild, White Fang, and Other Stories

The Call of the Wild, White Fang, and Other Stories The Call of the Wild and Selected Stories

The Call of the Wild and Selected Stories Jerry of the Islands

Jerry of the Islands Hearts of Three

Hearts of Three The House of Pride

The House of Pride Moon-Face and Other Stories

Moon-Face and Other Stories Children of the Frost

Children of the Frost South Sea Tales

South Sea Tales The Strength of the Strong

The Strength of the Strong The Jacket (The Star-Rover)

The Jacket (The Star-Rover) The Little Lady of the Big House

The Little Lady of the Big House John Barleycorn

John Barleycorn ADaugter of Snows

ADaugter of Snows The Mutiny of the Elsinore

The Mutiny of the Elsinore Northland Stories

Northland Stories Tales of the Fish Patrol

Tales of the Fish Patrol Call of the Wild and White Fang (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Call of the Wild and White Fang (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Valley of the Moon

The Valley of the Moon The Cruise of the Snark

The Cruise of the Snark The Game

The Game An Autobiography of Jack London

An Autobiography of Jack London