- Home

- Jack London

The Call of the Wild and Selected Stories Page 16

The Call of the Wild and Selected Stories Read online

Page 16

Nor could he wait the hour designated; for he was fifteen minutes ahead of time in rousing his guest. The young giant had stiffened badly, and brisk rubbing was necessary to bring him to his feet. He tottered painfully out of the cabin, to find his dogs harnessed and everything ready for the start. The company wished him good luck and a short chase, while Father Roubeau, hurriedly blessing him, led the stampede for the cabin; and small wonder, for it is not good to face seventy-four degrees below zero with naked ears and hands.

Malemute Kid saw him to the main trail, and there, gripping his hand heartily, gave him advice.

“You’ll find a hundred pounds of salmon eggs on the sled,” he said. “The dogs will go as far on that as with one hundred and fifty of fish, and you can’t get dog food at Pelly, as you probably expected.” The stranger started, and his eyes flashed, but he did not interrupt. “You can’t get an ounce of food for dog or man till you reach Five Fingers, and that’s a stiff two hundred miles. Watch out for open water on the Thirty Mile River, and be sure you take the big cutoff above Laberge.”

“How did you know it? Surely the news can’t be ahead of me already?”

“I don’t know it; and what’s more, I don’t want to know it. But you never owned that team you’re chasing. Sitka Charley sold it to them last spring. But he sized you up to me as square once, and I believe him. I’ve seen your face; I like it. And I’ve seen—why, damn you, hit the high places for salt water and that wife of yours, and—” Here the Kid unmittened and jerked out his sack.

“No; I don’t need it,” and the tears froze on his cheeks as he convulsively gripped Malemute Kid’s hand.

“Then don’t spare the dogs; cut them out of the traces as fast as they drop; buy them and think they’re cheap at ten dollars a pound. You can get them at Five Fingers, Little Salmon, and Hootalinqua. And watch out for wet feet,” was his parting advice. “Keep a-traveling up to twenty-five, but if it gets below that, build a fire and change your socks.”

Fifteen minutes had barely elapsed when the jingle of bells announced new arrivals. The door opened, and a mounted policeman of the Northwest Territory entered, followed by two half-breed dog drivers. Like Westondale, they were heavily armed and showed signs of fatigue. The half-breeds had been born to the trail and bore it easily; but the young policeman was badly exhausted. Still, the dogged obstinacy of his race held him to the pace he had set, and would hold him till he dropped in his tracks.

“When did Westondale pull out?” he asked. “He stopped here, didn’t he?” This was supererogatory, for the tracks told their own tale too well.

Malemute Kid had caught Belden’s eye, and he, scenting the wind, replied evasively, “A right peart while back.”

“Come, my man; speak up,” the policeman admonished.

“Yeh seem to want him right smart. Hez he ben gittin’ cantankerous down Dawson way?”

“Held up Harry McFarland’s for forty thousand; exchanged it at the P. C. store for a check on Seattle; and who’s to stop the cashing of it if we don’t overtake him? When did he pull out?”

Every eye suppressed its excitement, for Malemute Kid had given the cue, and the young officer encountered wooden faces on every hand.

Striding over to Prince, he put the question to him. Though it hurt him, gazing into the frank, earnest face of his fellow countryman, he replied inconsequentially on the state of the trail.

Then he espied Father Roubeau, who could not lie. “A quarter of an hour ago,” the priest answered; “but he had four hours’ rest for himself and dogs.”

“Fifteen minutes’ start, and he’s fresh! My God!” The poor fellow staggered back, half fainting from exhaustion and disappointment, murmuring something about the run from Dawson in ten hours and the dogs being played out.

Malemute Kid forced a mug of punch upon him; then he turned for the door, ordering the dog drivers to follow. But the warmth and promise of rest were too tempting, and they objected strenuously. The Kid was conversant with their French patois, and followed it anxiously.

They swore that the dogs were gone up; that Siwash and Babette would have to be shot before the first mile was covered; that the rest were almost as bad; and that it would be better for all hands to rest up.

“Lend me five dogs?” he asked, turning to Malemute Kid.

But the Kid shook his head.

“I’ll sign a check on Captain Constantine for five thousand—here’s my papers—I’m authorized to draw at my own discretion.”

Again the silent refusal.

“Then I’ll requisition them in the name of the Queen.”

Smiling incredulously, the Kid glanced at his well-stocked arsenal, and the Englishman, realizing his im potency, turned for the door. But, the dog drivers still objecting, he whirled upon them fiercely, calling them women and curs. The swart face of the older half-breed flushed angrily as he drew himself up and promised in good, round terms that he would travel his leader off his legs, and would then be delighted to plant him in the snow.

The young officer—and it required his whole will—walked steadily to the door, exhibiting a freshness he did not possess. But they all knew and appreciated his proud effort; nor could he veil the twinges of agony that shot across his face. Covered with frost, the dogs were curled up in the snow, and it was almost impossible to get them to their feet. The poor brutes whined under the stinging lash, for the dog drivers were angry and cruel; nor till Babette, the leader, was cut from the traces could they break out the sled and get under way.

“A dirty scoundrel and a liar!” “By gar! Him no good!” “A thief!” “Worse than an Indian!” It was evident that they were angry—first at the way they had been deceived; and second at the outraged ethics of the Northland, where honesty, above all, was man’s prime jewel. “An’ we gave the cuss a hand, after knowin’ what he’d did.” All eyes turned accusingly upon Malemute Kid, who rose from the corner where he had been making Babette comfortable, and silently emptied the bowl for a final round of punch.

“It’s a cold night, boys—a bitter cold night,” was the irrelevant commencement of his defense. “You’ve all traveled trail, and know what that stands for. Don’t jump a dog when he’s down. You’ve only heard one side. A whiter man than Jack Westondale never ate from the same pot nor stretched blanket with you or me. Last fall he gave his whole clean-up, forty thousand, to Joe Castrell, to buy in on Dominion. Today he’d be a millionaire. But while he stayed behind at Circle City, taking care of his partner with the scurvy, what does Castrell do? Goes into McFarland’s, jumps the limit, and drops the whole sack. Found him dead in the snow the next day. And poor Jack laying his plans to go out this winter to his wife and the boy he’s never seen. You’ll notice he took exactly what his partner lost—forty thousand. Well, he’s gone out; and what are you going to do about it?”

The Kid glanced round the circle of his judges, noted the softening of their faces, then raised his mug aloft. “So a health to the man on trail this night; may his grub hold out; may his dogs keep their legs; may his matches never miss fire. God prosper him; good luck go with him; and—”

“Confusion to the Mounted Police!” cried Bettles, to the crash of the empty cups.

To Build a Fire

Day had broken cold and gray, exceedingly cold and gray, when the man turned aside from the main Yukon trail and climbed the high earth bank, where a dim and little-traveled trail led eastward through the fat spruce timberland. It was a steep bank, and he paused for breath at the top, excusing the act to himself by looking at his watch. It was nine o’clock. There was no sun nor hint of sun, though there was not a cloud in the sky. It was a clear day, and yet there seemed an intangible pall over the face of things, a subtle gloom that made the day dark, and that was due to the absence of sun. This fact did not worry the man. He was used to the lack of sun. It had been days since he had seen the sun, and he knew that a few more days must pass before that cheerful orb, due south, would just peep above the sky line and dip i

mmediately from view.

The man flung a look back along the way he had come. The Yukon lay a mile wide and hidden under three feet of ice. On top of this ice were as many feet of snow. It was all pure white, rolling in gentle undulations where the ice jams of the freeze-up had formed. North and south, as far as his eye could see, it was unbroken white, save for a dark hairline that curved and twisted from around the spruce-covered island to the south, and that curved and twisted away into the north, where it disappeared behind another spruce-covered island. This dark hairline was the trail—the main trail—that led south five hundred miles to the Chilkoot Pass, Dyea, and salt water; and that led north seventy miles to Dawson, and still on to the north a thousand miles to Nulato, and finally to St. Michael, on Bering Sea, a thousand miles and half a thousand more.

But all this—the mysterious, far-reaching hairline trail, the absence of sun from the sky, the tremendous cold, and the strangeness and weirdness of it all—made no impression on the man. It was not because he was long used to it. He was a newcomer in the land, a chechaquo, and this was his first winter. The trouble with him was that he was without imagination. He was quick and alert in the things of life, but only in the things, and not in the significance. Fifty degrees below zero meant eighty-odd degrees of frost. Such fact impressed him as being cold and uncomfortable, and that was all. It did not lead him to meditate upon his frailty as a creature of temperature, and upon man’s frailty in general, able only to live within certain narrow limits of heat and cold; and from there on it did not lead him to the conjectural field of immortality and man’s place in the universe. Fifty degrees below zero stood for a bite of frost that hurt and that must be guarded against by the use of mittens, ear flaps, warm moccasins, and thick socks. Fifty degrees below zero was to him just precisely fifty degrees below zero. That there should be anything more to it than that was a thought that never entered his head.

As he turned to go on, he spat speculatively. There was a sharp, explosive crackle that startled him. He spat again. And again, in the air, before it could fall to the snow, the spittle crackled. He knew that at fifty below spittle crackled on the snow, but this spittle had crackled in the air. Undoubtedly it was colder than fifty below—how much colder he did not know. But the temperature did not matter. He was bound for the old claim on the left fork of Henderson Creek, where the boys were already. They had come over across the divide from the Indian Creek country, while he had come the roundabout way to take a look at the possibilities of getting out logs in the spring from the islands in the Yukon. He would be into camp by six o’clock; a bit after dark, it was true, but the boys would be there, a fire would be going, and a hot supper would be ready. As for lunch, he pressed his hand against the protruding bundle under his jacket. It was also under his shirt, wrapped up in a handkerchief and lying against the naked skin. It was the only way to keep the biscuits from freezing. He smiled agreeably to himself as he thought of those biscuits, each cut open and sopped in bacon grease, and each enclosing a generous slice of fried bacon.

He plunged in among the big spruce trees. The trail was faint. A foot of snow had fallen since the last sled had passed over, and he was glad he was without a sled, traveling light. In fact, he carried nothing but the lunch wrapped in the handkerchief. He was surprised, however, at the cold. It certainly was cold, he concluded, as he rubbed his numb nose and cheekbones with his mittened hand. He was a warm-whiskered man, but the hair on his face did not protect the high cheekbones and the eager nose that thrust itself aggressively into the frosty air.

At the man’s heels trotted a dog, a big native husky, the proper wolf dog, gray-coated and without any visible or temperamental difference from its brother the wild wolf. The animal was depressed by the tremendous cold. It knew that it was no time for traveling. Its instinct told it a truer tale than was told to the man by the man’s judgment. In reality, it was not merely colder than fifty below zero; it was colder than sixty below, than seventy below. It was seventy-five below zero. Since the freezing point is thirty-two above zero, it meant that one hundred and seven degrees of frost obtained. The dog did not know anything about thermometers. Possibly in its brain there was no sharp consciousness of a condition of very cold such as was in the man’s brain. But the brute had its instinct. It experienced a vague but menacing apprehension that subdued it and made it slink along at the man’s heels, and that made it question eagerly every unwonted movement of the man as if expecting him to go into camp or to seek shelter somewhere and build a fire. The dog had learned fire, and it wanted fire, or else to burrow under the snow and cuddle its warmth away from the air.

The frozen moisture of its breathing had settled on its fur in a fine powder of frost, and especially were its jowls, muzzle, and eyelashes whitened by its crystaled breath. The man’s red beard and mustache were likewise frosted, but more solidly, the deposit taking the form of ice and increasing with every warm, moist breath he exhaled. Also, the man was chewing tobacco, and the muzzle of ice held his lips so rigidly that he was unable to clear his chin when he expelled the juice. The result was that a crystal beard of the color and solidity of amber was increasing its length on his chin. If he fell down it would shatter itself, like glass, into brittle fragments. But he did not mind the appendage. It was the penalty all tobacco chewers paid in that country, and he had been out before in two cold snaps. They had not been so cold as this, he knew, but by the spirit thermometer at Sixty Mile he knew they had been registered at fifty below and at fifty-five.

He held on through the level stretch of woods for several miles, crossed a wide flat of nigger heads, and dropped down a bank to the frozen bed of a small stream. This was Henderson Creek, and he knew he was ten miles from the forks. He looked at his watch. It was ten o’clock. He was making four miles an hour, and he calculated that he would arrive at the forks at half-past twelve. He decided to celebrate that event by eating his lunch there.

The dog dropped in again at his heels, with a tail drooping discouragement, as the man swung along the creek bed. The furrow of the old sled trail was plainly visible, but a dozen inches of snow covered the marks of the last runners. In a month no man had come up or down that silent creek. The man held steadily on. He was not much given to thinking, and just then particularly he had nothing to think about save that he would eat lunch at the forks and that at six o’clock he would be in camp with the boys. There was nobody to talk to; and, had there been, speech would have been impossible because of the ice muzzle on his mouth. So he continued monotonously to chew tobacco and to increase the length of his amber beard.

Once in a while the thought reiterated itself that it was very cold and that he had never experienced such cold. As he walked along he rubbed his cheekbones and nose with the back of his mittened hand. He did this automatically, now and again changing hands. But, rub as he would, the instant he stopped his cheekbones went numb, and the following instant the end of his nose went numb. He was sure to frost his cheeks; he knew that, and experienced a pang of regret that he had not devised a nose strap of the sort Bud wore in cold snaps. Such a strap passed across the cheeks, as well, and saved them. But it didn’t matter much, after all. What were frosted cheeks? A bit painful, that was all; they were never serious.

Empty as the man’s mind was of thoughts, he was keenly observant, and he noticed the changes in the creek, the curves and bends and timber jams, and always he sharply noted where he placed his feet. Once, coming around a bend, he shied abruptly, like a startled horse, curved away from the place where he had been walking, and retreated several paces back along the trail. The creek he knew was frozen clear to the bottom—no creek could contain water in that arctic winter—but he knew also that there were springs that bubbled out from the hillsides and ran along under the snow and on top the ice of the creek. He knew that the coldest snaps never froze these springs, and he knew likewise their danger. They were traps. They hid pools of water under the snow that might be three inches deep, or three feet. Sometimes a sk

in of ice half an inch thick covered them, and in turn was covered by the snow. Sometimes there were alternate layers of water and ice skin, so that when one broke through he kept on breaking through for a while, sometimes wetting himself to the waist.

That was why he had shied in such panic. He had felt the give under his feet and heard the crackle of a snow-hidden ice skin. And to get his feet wet in such a temperature meant trouble and danger. At the very least it meant delay, for he would be forced to stop and build a fire, and under its protection to bare his feet while he dried his socks and moccasins. He stood and studied the creek bed and its banks, and decided that the flow of water came from the right. He reflected awhile, rubbing his nose and cheeks, then skirted to the left, stepping gingerly and testing the footing for each step. Once clear of the danger, he took a fresh chew of tobacco and swung along at his four-mile gait.

In the course of the next two hours he came upon several similar traps. Usually the snow above the hidden pools had a sunken, candied appearance that advertised the danger. Once again, however, he had a close call; and once, suspecting danger, he compelled the dog to go on in front. The dog did not want to go. It hung back until the man shoved it forward, and then it went quickly across the white, unbroken surface. Suddenly it broke through, floundered to one side, and got away to firmer footing. It had wet its forefeet and legs, and almost immediately the water that clung to it turned to ice. It made quick efforts to lick the ice off its legs, then dropped down in the snow and began to bite out the ice that had formed between the toes. This was a matter of instinct. To permit the ice to remain would mean sore feet. It did not know this. It merely obeyed the mysterious prompting that arose from the deep crypts of its being. But the man knew, having achieved a judgment on the subject, and he removed the mitten from his right hand and helped tear out the ice particles. He did not expose his fingers more than a minute, and was astonished at the swift numbness that smote them. It certainly was cold. He pulled on the mitten hastily, and beat the hand savagely across his chest.

The Son of the Wolf

The Son of the Wolf The Iron Heel

The Iron Heel Before Adam

Before Adam Smoke Bellew

Smoke Bellew The Call of the Wild

The Call of the Wild The Valley of the Moon Jack London

The Valley of the Moon Jack London Burning Daylight

Burning Daylight The Sea Wolf

The Sea Wolf White Fang

White Fang A Daughter of the Snows

A Daughter of the Snows The Night-Born

The Night-Born A Son Of The Sun

A Son Of The Sun Dutch Courage and Other Stories

Dutch Courage and Other Stories The People of the Abyss

The People of the Abyss Michael, Brother of Jerry

Michael, Brother of Jerry Love of Life, and Other Stories

Love of Life, and Other Stories Lost Face

Lost Face The Road

The Road Love of Life

Love of Life The Turtles of Tasman

The Turtles of Tasman The Cruise of The Dazzler

The Cruise of The Dazzler The Heathen

The Heathen The Scab

The Scab The Faith of Men

The Faith of Men Adventure

Adventure The Assassination Bureau, Ltd.

The Assassination Bureau, Ltd. The Call of the Wild, White Fang, and Other Stories

The Call of the Wild, White Fang, and Other Stories The Call of the Wild and Selected Stories

The Call of the Wild and Selected Stories Jerry of the Islands

Jerry of the Islands Hearts of Three

Hearts of Three The House of Pride

The House of Pride Moon-Face and Other Stories

Moon-Face and Other Stories Children of the Frost

Children of the Frost South Sea Tales

South Sea Tales The Strength of the Strong

The Strength of the Strong The Jacket (The Star-Rover)

The Jacket (The Star-Rover) The Little Lady of the Big House

The Little Lady of the Big House John Barleycorn

John Barleycorn ADaugter of Snows

ADaugter of Snows The Mutiny of the Elsinore

The Mutiny of the Elsinore Northland Stories

Northland Stories Tales of the Fish Patrol

Tales of the Fish Patrol Call of the Wild and White Fang (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Call of the Wild and White Fang (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Valley of the Moon

The Valley of the Moon The Cruise of the Snark

The Cruise of the Snark The Game

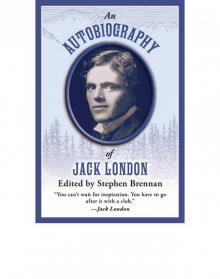

The Game An Autobiography of Jack London

An Autobiography of Jack London