- Home

- Jack London

The Turtles of Tasman Page 13

The Turtles of Tasman Read online

Page 13

"What's Rocky up an' do? He goes downside of log, reaches over with his knife, an' begins slashin'. But he can only reach bear's rump, an' dawgs bein' ruined fast, one-two-three time. Rocky gets desperate. He don't like to lose his dawgs. He jumps on top log, grabs bear by the slack of the rump, an' heaves over back'ard right over top of that log. Down they go, kit an' kaboodle, twenty feet, bear, dawgs, an' Rocky, slidin', cussin', an' scratchin', ker-plump into ten feet of water in the bed of stream. They all swum out different ways. Nope, he didn't get the bear, but he saved the dawgs. That's Rocky. They's no stoppin' him when his mind's set."

It was at the next camp that Linday heard how Rocky had come to be injured.

"I'd ben up the draw, about a mile from the cabin, lookin' for a piece of birch likely enough for an axe-handle. Comin' back I heard the darndest goings-on where we had a bear trap set. Some trapper had left the trap in an old cache an' Rocky'd fixed it up. But the goings-on. It was Rocky an' his brother Harry. First I'd hear one yell and laugh, an' then the other, like it was some game. An' what do you think the fool game was? I've saw some pretty nervy cusses down in Curry County, but they beat all. They'd got a whoppin' big panther in the trap an' was takin' turns rappin' it on the nose with a light stick. But that wa'n't the point. I just come out of the brush in time to see Harry rap it. Then he chops six inches off the stick an' passes it to Rocky. You see, that stick was growin' shorter all the time. It ain't as easy as you think. The panther'd slack back an' hunch down an' spit, an' it was mighty lively in duckin' the stick. An' you never knowed when it'd jump. It was caught by the hind leg, which was curious, too, an' it had some slack I'm tellin' you.

"It was just a game of dare they was playin', an' the stick gettin' shorter an' shorter an' the panther madder 'n madder. Bimeby they wa'n't no stick left-only a nubbin, about four inches long, an' it was Rocky's turn. 'Better quit now,' says Harry. 'What for?' says Rocky. 'Because if you rap him again they won't be no stick left for me,' Harry answers. 'Then you'll quit an' I win,' says Rocky with a laugh, an' goes to it.

"An' I don't want to see anything like it again. That cat'd bunched back an' down till it had all of six feet slack in its body. An' Rocky's stick four inches long. The cat got him. You couldn't see one from t'other. No chance to shoot. It was Harry, in the end, that got his knife into the panther's jugular."

"If I'd known how he got it I'd never have come," was Linday's comment.

Daw nodded concurrence.

"That's what she said. She told me sure not to whisper how it happened."

"Is he crazy?" Linday demanded in his wrath.

"They're all crazy. Him an' his brother are all the time devilin' each other to tom-fool things. I seen them swim the riffle last fall, bad water an' mush-ice runnin'-on a dare. They ain't nothin' they won't tackle. An' she's 'most as bad. Not afraid some herself. She'll do anything Rocky'll let her. But he's almighty careful with her. Treats her like a queen. No camp-work or such for her. That's why another man an' me are hired on good wages. They've got slathers of money an' they're sure dippy on each other. 'Looks like good huntin',' says Rocky, when they struck that section last fall. 'Let's make a camp then,' says Harry. An' me all the time thinkin' they was lookin' for gold. Ain't ben a prospect pan washed the whole winter."

Linday's anger mounted. "I haven't any patience with fools. For two cents I'd turn back."

"No you wouldn't," Daw assured him confidently. "They ain't enough grub to turn back, an' we'll be there to-morrow. Just got to cross that last divide an' drop down to the cabin. An' they's a better reason. You're too far from home, an' I just naturally wouldn't let you turn back."

Exhausted as Linday was, the flash in his black eyes warned Daw that he had overreached himself. His hand went out.

"My mistake, Doc. Forget it. I reckon I'm gettin' some cranky what of losin' them dawgs."

III

Not one day, but three days later, the two men, after being snowed in on the summit by a spring blizzard, staggered up to a cabin that stood in a fat bottom beside the roaring Little Peco. Coming in from the bright sunshine to the dark cabin, Linday observed little of its occupants. He was no more than aware of two men and a woman. But he was not interested in them. He went directly to the bunk where lay the injured man. The latter was lying on his back, with eyes closed, and Linday noted the slender stencilling of the brows and the kinky silkiness of the brown hair. Thin and wan, the face seemed too small for the muscular neck, yet the delicate features, despite their waste, were firmly moulded.

"What dressings have you been using?" Linday asked of the woman.

"Corrosive, sublimate, regular solution," came the answer.

He glanced quickly at her, shot an even quicker glance at the face of the injured man, and stood erect. She breathed sharply, abruptly biting off the respiration with an effort of will. Linday turned to the men.

"You clear out-chop wood or something. Clear out."

One of them demurred.

"This is a serious case," Linday went on. "I want to talk to his wife."

"I'm his brother," said the other.

To him the woman looked, praying him with her eyes. He nodded reluctantly and turned toward the door.

"Me, too?" Daw queried from the bench where he had flung himself down.

"You, too."

Linday busied himself with a superficial examination of the patient while the cabin was emptying.

"So?" he said. "So that's your Rex Strang."

She dropped her eyes to the man in the bunk as if to reassure herself of his identity, and then in silence returned Linday's gaze.

"Why don't you speak?"

She shrugged her shoulders. "What is the use? You know it is Rex Strang."

"Thank you. Though I might remind you that it is the first time I have ever seen him. Sit down." He waved her to a stool, himself taking the bench. "I'm really about all in, you know. There's no turnpike from the Yukon here."

He drew a penknife and began extracting a thorn from his thumb.

"What are you going to do?" she asked, after a minute's wait.

"Eat and rest up before I start back."

"What are you going to do about…" She inclined her head toward the unconscious man.

"Nothing."

She went over to the bunk and rested her fingers lightly on the tight-curled hair.

"You mean you will kill him," she said slowly. "Kill him by doing nothing, for you can save him if you will."

"Take it that way." He considered a moment, and stated his thought with a harsh little laugh. "From time immemorial in this weary old world it has been a not uncommon custom so to dispose of wife-stealers."

"You are unfair, Grant," she answered gently. "You forget that I was willing and that I desired. I was a free agent. Rex never stole me. It was you who lost me. I went with him, willing and eager, with song on my lips. As well accuse me of stealing him. We went together."

"A good way of looking at it," Linday conceded. "I see you are as keen a thinker as ever, Madge. That must have bothered him."

"A keen thinker can be a good lover-"

"And not so foolish," he broke in.

"Then you admit the wisdom of my course?"

He threw up his hands. "That's the devil of it, talking with clever women. A man always forgets and traps himself. I wouldn't wonder if you won him with a syllogism."

Her reply was the hint of a smile in her straight-looking blue eyes and a seeming emanation of sex pride from all the physical being of her.

"No, I take that back, Madge. If you'd been a numbskull you'd have won him, or any one else, on your looks, and form, and carriage. I ought to know. I've been through that particular mill, and, the devil take me, I'm not through it yet."

His speech was quick and nervous and irritable, as it always was, and, as she knew, it was always candid. She took her cue from his last remark.

"Do you remember Lake Geneva?"

"I ought to. I was rather absurdly happy."<

br />

She nodded, and her eyes were luminous. "There is such a thing as old sake. Won't you, Grant, please, just remember back… a little… oh, so little… of what we were to each other… then?"

"Now you're taking advantage," he smiled, and returned to the attack on his thumb. He drew the thorn out, inspected it critically, then concluded. "No, thank you. I'm not playing the Good Samaritan."

"Yet you made this hard journey for an unknown man," she urged.

His impatience was sharply manifest. "Do you fancy I'd have moved a step had I known he was my wife's lover?"

"But you are here… now. And there he lies. What are you going to do?"

"Nothing. Why should I? I am not at the man's service. He pilfered me."

She was about to speak, when a knock came on the door.

"Get out!" he shouted.

"If you want any assistance-"

"Get out! Get a bucket of water! Set it down outside!"

"You are going to…?" she began tremulously.

"Wash up."

She recoiled from the brutality, and her lips tightened.

"Listen, Grant," she said steadily. "I shall tell his brother. I know the Strang breed. If you can forget old sake, so can I. If you don't do something, he'll kill you. Why, even Tom Daw would if I asked."

"You should know me better than to threaten," he reproved gravely, then added, with a sneer: "Besides, I don't see how killing me will help your Rex Strang."

She gave a low gasp, closed her lips tightly, and watched his quick eyes take note of the trembling that had beset her.

"It's not hysteria, Grant," she cried hastily and anxiously, with clicking teeth. "You never saw me with hysteria. I've never had it. I don't know what it is, but I'll control it. I am merely beside myself. It's partly anger-with you. And it's apprehension and fear. I don't want to lose him. I do love him, Grant. He is my king, my lover. And I have sat here beside him so many dreadful days now. Oh, Grant, please, please."

"Just nerves," he commented drily. "Stay with it. You can best it. If you were a man I'd say take a smoke."

She went unsteadily back to the stool, where she watched him and fought for control. From the rough fireplace came the singing of a cricket. Outside two wolf-dogs bickered. The injured man's chest rose and fell perceptibly under the fur robes. She saw a smile, not altogether pleasant, form on Linday's lips.

"How much do you love him?" he asked.

Her breast filled and rose, and her eyes shone with a light unashamed and proud. He nodded in token that he was answered.

"Do you mind if I take a little time?" He stopped, casting about for the way to begin. "I remember reading a story-Herbert Shaw wrote it, I think. I want to tell you about it. There was a woman, young and beautiful; a man magnificent, a lover of beauty and a wanderer. I don't know how much like your Rex Strang he was, but I fancy a sort of resemblance. Well, this man was a painter, a bohemian, a vagabond. He kissed-oh, several times and for several weeks-and rode away. She possessed for him what I thought you possessed for me… at Lake Geneva. In ten years she wept the beauty out of her face. Some women turn yellow, you know, when grief upsets their natural juices.

"Now it happened that the man went blind, and ten years afterward, led as a child by the hand, he stumbled back to her. There was nothing left. He could no longer paint. And she was very happy, and glad he could not see her face. Remember, he worshipped beauty. And he continued to hold her in his arms and believe in her beauty. The memory of it was vivid in him. He never ceased to talk about it, and to lament that he could not behold it.

"One day he told her of five great pictures he wished to paint. If only his sight could be restored to paint them, he could write finis and be content. And then, no matter how, there came into her hands an elixir. Anointed on his eyes, the sight would surely and fully return."

Linday shrugged his shoulders.

"You see her struggle. With sight, he could paint his five pictures. Also, he would leave her. Beauty was his religion. It was impossible that he could abide her ruined face. Five days she struggled. Then she anointed his eyes."

Linday broke off and searched her with his eyes, the high lights focused sharply in the brilliant black.

"The question is, do you love Rex Strang as much as that?"

"And if I do?" she countered.

"Do you?"

"Yes."

"You can sacrifice? You can give him up?"

Slow and reluctant was her "Yes."

"And you will come with me?"

"Yes." This time her voice was a whisper. "When he is well-yes."

"You understand. It must be Lake Geneva over again. You will be my wife."

She seemed to shrink and droop, but her head nodded.

"Very well." He stood up briskly, went to his pack, and began unstrapping. "I shall need help. Bring his brother in. Bring them all in. Boiling water-let there be lots of it. I've brought bandages, but let me see what you have in that line.-Here, Daw, build up that fire and start boiling all the water you can.-Here you," to the other man, "get that table out and under the window there. Clean it; scrub it; scald it. Clean, man, clean, as you never cleaned a thing before. You, Mrs. Strang, will be my helper. No sheets, I suppose. Well, we'll manage somehow.-You're his brother, sir. I'll give the an?sthetic, but you must keep it going afterward. Now listen, while I instruct you. In the first place-but before that, can you take a pulse?…"

IV

Noted for his daring and success as a surgeon, through the days and weeks that followed Linday exceeded himself in daring and success. Never, because of the frightful mangling and breakage, and because of the long delay, had he encountered so terrible a case. But he had never had a healthier specimen of human wreck to work upon. Even then he would have failed, had it not been for the patient's catlike vitality and almost uncanny physical and mental grip on life.

There were days of high temperature and delirium; days of heart-sinking when Strang's pulse was barely perceptible; days when he lay conscious, eyes weary and drawn, the sweat of pain on his face. Linday was indefatigable, cruelly efficient, audacious and fortunate, daring hazard after hazard and winning. He was not content to make the man live. He devoted himself to the intricate and perilous problem of making him whole and strong again.

"He will be a cripple?" Madge queried.

"He will not merely walk and talk and be a limping caricature of his former self," Linday told her. "He shall run and leap, swim riffles, ride bears, fight panthers, and do all things to the top of his fool desire. And, I warn you, he will fascinate women just as of old. Will you like that? Are you content? Remember, you will not be with him."

"Go on, go on," she breathed. "Make him whole. Make him what he was."

More than once, whenever Strang's recuperation permitted, Linday put him under the an?sthetic and did terrible things, cutting and sewing, rewiring and connecting up the disrupted organism. Later, developed a hitch in the left arm. Strang could lift it so far, and no farther. Linday applied himself to the problem. It was a case of more wires, shrunken, twisted, disconnected. Again it was cut and switch and ease and disentangle. And all that saved Strang was his tremendous vitality and the health of his flesh.

"You will kill him," his brother complained. "Let him be. For God's sake let him be. A live and crippled man is better than a whole and dead one."

Linday flamed in wrath. "You get out! Out of this cabin with you till you can come back and say that I make him live. Pull-by God, man, you've got to pull with me with all your soul. Your brother's travelling a hairline razor-edge. Do you understand? A thought can topple him off. Now get out, and come back sweet and wholesome, convinced beyond all absoluteness that he will live and be what he was before you and he played the fool together. Get out, I say."

The brother, with clenched hands and threatening eyes, looked to Madge for counsel.

"Go, go, please," she begged. "He is right. I know he is right."

Another time, when Strang

's condition seemed more promising, the brother said:

"Doc, you're a wonder, and all this time I've forgotten to ask your name."

"None of your damn business. Don't bother me. Get out."

The mangled right arm ceased from its healing, burst open again in a frightful wound.

"Necrosis," said Linday.

"That does settle it," groaned the brother.

"Shut up!" Linday snarled. "Get out! Take Daw with you. Take Bill, too. Get rabbits-alive-healthy ones. Trap them. Trap everywhere."

"How many?" the brother asked.

"Forty of them-four thousand-forty thousand-all you can get. You'll help me, Mrs. Strang. I'm going to dig into that arm and size up the damage. Get out, you fellows. You for the rabbits."

And he dug in, swiftly, unerringly, scraping away disintegrating bone, ascertaining the extent of the active decay.

"It never would have happened," he told Madge, "if he hadn't had so many other things needing vitality first. Even he didn't have vitality enough to go around. I was watching it, but I had to wait and chance it. That piece must go. He could manage without it, but rabbit-bone will make it what it was."

From the hundreds of rabbits brought in, he weeded out, rejected, selected, tested, selected and tested again, until he made his final choice. He used the last of his chloroform and achieved the bone-graft-living bone to living bone, living man and living rabbit immovable and indissolubly bandaged and bound together, their mutual processes uniting and reconstructing a perfect arm.

And through the whole trying period, especially as Strang mended, occurred passages of talk between Linday and Madge. Nor was he kind, nor she rebellious.

"It's a nuisance," he told her. "But the law is the law, and you'll need a divorce before we can marry again. What do you say? Shall we go to Lake Geneva?"

"As you will," she said.

And he, another time: "What the deuce did you see in him anyway? I know he had money. But you and I were managing to get along with some sort of comfort. My practice was averaging around forty thousand a year then-I went over the books afterward. Palaces and steam yachts were about all that was denied you."

The Son of the Wolf

The Son of the Wolf The Iron Heel

The Iron Heel Before Adam

Before Adam Smoke Bellew

Smoke Bellew The Call of the Wild

The Call of the Wild The Valley of the Moon Jack London

The Valley of the Moon Jack London Burning Daylight

Burning Daylight The Sea Wolf

The Sea Wolf White Fang

White Fang A Daughter of the Snows

A Daughter of the Snows The Night-Born

The Night-Born A Son Of The Sun

A Son Of The Sun Dutch Courage and Other Stories

Dutch Courage and Other Stories The People of the Abyss

The People of the Abyss Michael, Brother of Jerry

Michael, Brother of Jerry Love of Life, and Other Stories

Love of Life, and Other Stories Lost Face

Lost Face The Road

The Road Love of Life

Love of Life The Turtles of Tasman

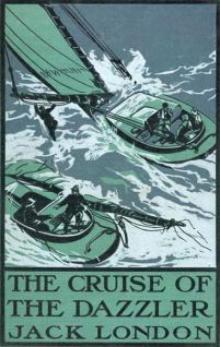

The Turtles of Tasman The Cruise of The Dazzler

The Cruise of The Dazzler The Heathen

The Heathen The Scab

The Scab The Faith of Men

The Faith of Men Adventure

Adventure The Assassination Bureau, Ltd.

The Assassination Bureau, Ltd. The Call of the Wild, White Fang, and Other Stories

The Call of the Wild, White Fang, and Other Stories The Call of the Wild and Selected Stories

The Call of the Wild and Selected Stories Jerry of the Islands

Jerry of the Islands Hearts of Three

Hearts of Three The House of Pride

The House of Pride Moon-Face and Other Stories

Moon-Face and Other Stories Children of the Frost

Children of the Frost South Sea Tales

South Sea Tales The Strength of the Strong

The Strength of the Strong The Jacket (The Star-Rover)

The Jacket (The Star-Rover) The Little Lady of the Big House

The Little Lady of the Big House John Barleycorn

John Barleycorn ADaugter of Snows

ADaugter of Snows The Mutiny of the Elsinore

The Mutiny of the Elsinore Northland Stories

Northland Stories Tales of the Fish Patrol

Tales of the Fish Patrol Call of the Wild and White Fang (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Call of the Wild and White Fang (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Valley of the Moon

The Valley of the Moon The Cruise of the Snark

The Cruise of the Snark The Game

The Game An Autobiography of Jack London

An Autobiography of Jack London